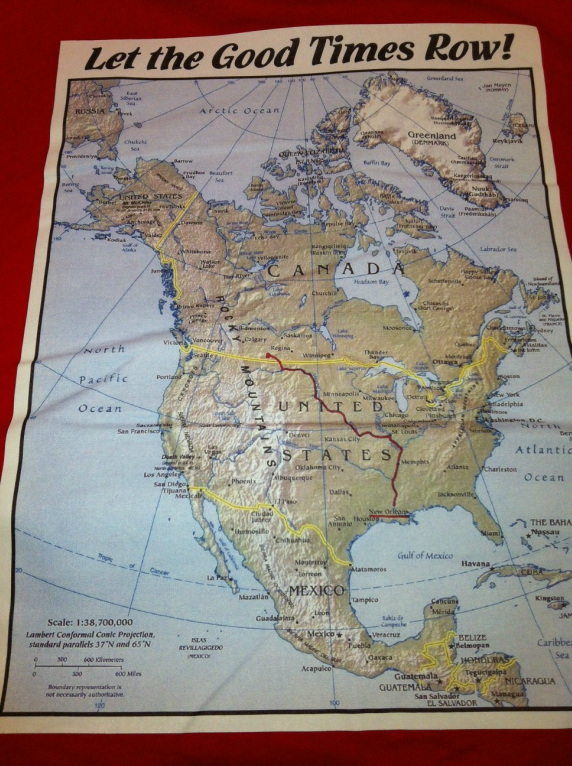

Part 2. On the Mississippi River to New Orleans

Arriving at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers was a major milestone. It marked the end of four months on the Missouri River and signalled the transition to the final river of the journey, the Mighty Mississippi.

The confluence is located a few miles north of St. Louis, a city I left Nov. 21, which was the two-year anniversary of M'Nonc Mitch's passing. On the 22nd, I arrived in Crystal City, Missouri where I had planned to get groceries and send a few articles. When I saw the pic-nic shelter at the Plattin Rock Boat Club located along the Mississippi, I knew I found my campsite. Not only did it provide shelter from the rain, but it had power outlets and lights. Having been limited to candles and flashlights for most of the trip, I enjoyed robbing the night of its darkness.

I met several members of the boat club, including Dave Hanley who gave me a replacement paddle for the one I broke on the Missouri River. Dave has helped many paddlers on their way to New Orleans or the Gulf of Mexico.

The Mississippi River was exceptionally low and the current was weak. This was the result of the severe and catastrophic drought that brutalized the mid-west United States that summer and continued into the fall. When planning Canoe to New Orleans, I had expected the current to be much stronger and had hoped to spend Christmas in New Orleans. This was no longer possible. To make matters worse, on Nov. 23 the Army Corps of Engineers greatly reduced the flow from Gavin's Point Dam on the Missouri River. This cheated the Mississippi of water from one of its most important tributaries. The dam restriction weakened the current and caused water levels to free-fall. Some nights, the river would drop one to two feet, to say nothing of daytime drops which are harder to notice.

Because the water was historically low, barges were only loaded to 3/4 capacity and word on the river was that barge traffic between St. Louis and Cairo, Illinois would soon be halted and that all barges would be banned from the entire river Dec. 22. I was told such a closure had never occurred in the history of commercial shipping on the Mississippi. Such were the water levels.

To compound the slow progress because of the anemic current, I was also being delayed by thick morning fog that would linger until noon leaving only four to five hours of light from the short autumn days. The determined south wind further slowed my forward advance. For the last 365 miles on the Missouri, I had gotten into a rhythm and I was used to clear, cold days with strong current that allowed me to consistently paddle 20 to 35 miles a day with a high of 42 miles. During my first week on the Mighty Mississippi, I averaged only a disappointing 13 miles a day.

I was frustrated by the slow progress and I was concerned my trip could take much longer than planned, but I decided to delay worrying until I reached Cairo, which is where the Ohio River, the Mississippi's foremost tributary, would increase the flow, or so I hoped. The Ohio drains Eastern states that weren't impacted by the drought.

On Nov. 25, I stopped in Sainte Genevieve, Missouri. Since high school, I've wondered why so many places in Missouri have French names. I decided to explore one and find out. I toured the Louis Bolduc house where I learned from my tour guide that many French-Canadians came to the area in the 1700s. The economy of the time included farming as well as mining lead and salt. Louis Bolduc was from Quebec. He built his home in 1792 and members of his family lived there until 1948 at which point the house was restored and became a museum. I met a lot of nice people in Ste. Genevieve and this gave me a boost of enthusiasm despite the difficult paddling.

Beyond Ste. Genevieve, the wind co-operated more and I was able to increase my daily average to 20 miles, but in certain locations the river bed was exposed and in some places the Mississippi was too shallow to even float a canoe. Like the barges, I religiously tried to stay in the deepest water.

As you see, barges weren't the only thing I had to share the river with.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Nwu-Er_7TI

I stopped in Cape Girardeau Nov. 30 and asked two women for directions to the grocery store. The elderly woman didn't know and she asked her middle-aged daughter-in-law who in turn asked me if I was on foot. When I said I was, the mother-in-law, Dolores, 82, offered me a ride. Then Daughter-in-Law said, "If you do anything to hurt her I'll get you." I laughed, but knew she was serious. I didn't take offence given the size of my beard and the fact that I smelled like several campfires, "Dolores, you must be a good person," I replied, "Daughters-in-law don't usually care for their mothers-in-law that much."

At the grocery store, we talked about her grandkids, her career as a Grade 6 teacher and my uncle Mitch. While in the produce department, her cell phone rang. I pretended not to listen, but I knew who was calling. "I'm fine," Dolores said, "We're having a wonderful conversation."

On Dec. 3, I reached the Ohio River. The wide expanse of water at the confluence was being churned by strong gusts and during the strongest I was unable to control my canoe. Not wanting to be blown into the path of a barge, I went to shore and set up camp in a stand of dense willows where I waited for morning. Soon, I would know if the Ohio was making the Mississippi flow faster.

The Ohio didn't disappoint me. From the confluence, I made good progress. On Dec. 4, I arrived in Kentucky and on the 5th I was in Tennessee. Passing from Illinois, to Kentucky and then into Tennessee, all in the span of a few days, encouraged me and made me feel like I was making headway.

By Dec. 8, I arrived in Caruthersville, Missouri. I needed a pair of waterproof gloves and went to the sporting goods store. The owner was about 70 and his six-year-old granddaughter was there. She didn't call him grandpa. Instead, she called him "Big Daddy." Her choice of words meant I was getting close to the South. The menu at the restaurant reflected this as well and featured collar greens, country fried steak and corn bread. The people spoke with the long Southern drawl.

Technically, Missouri is considered a Mid-West state, but during the Civil War it was a microcosm of the larger conflict. The northern and southern portions of the state were at war with each other. Missouri is where the transition to the South occurs.

Very heavy rain was in the overnight forecast and I looked for a spot to shelter my canoe, which I had named Hadley, so that it wouldn't fill with rainwater. I found cover under one of the two walkways that extend from shore to a river boat casino named Lady Luck. As I was preparing to drop anchor, a man on the walkway asked where I was from. When I answered Canada, he replied, "Makes sense, there's no hockey this season so there's nothing better to do in Canada." Jeremy Odell is one of the casino managers. He gave me a $20 voucher for the restaurant and $10 cash for drinks.

That night, the rain poured down mightily. And still the river went down, but the next night it began to rise. The current increased and in one narrow spot it propelled me to 10 mph. Although this was only for a few hundred yards, the increase to my morale was huge.

On Dec. 10, I exited Missouri. Tennessee was now on the east bank and Arkansas on the west. I was in the South. The weather improved and it was a pleasure to be on the river.

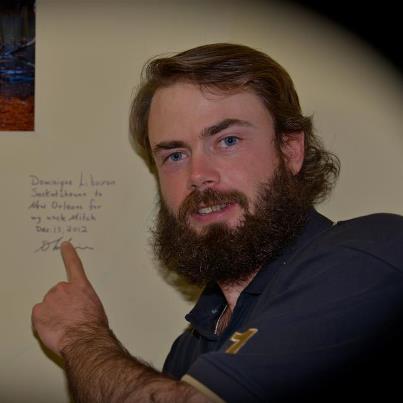

As I entered Memphis on Dec. 13, I saw a white-bearded man on the bank. He flailed his arm and obviously wanted to get my attention. I looked closer and saw a camera. The bearded stranger must have wanted a picture. Then he cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted, "Are you Dom?" I shouted back I was. "There's a boat ramp over there." He pointed downstream 100 yards.

I was surprised anyone in Memphis knew me. Previous to the trip, I'd never been south of the Great Lakes. However, I suspected I knew the white-bearded stranger's identity. I had heard of him through the paddlers' underground, the network of canoeing and kayaking enthusiasts, but I thought he lived somewhere along the Missouri River.

I eased Hadley into the slack water at the foot of the boat ramp. The Beard snapped a few pictures. I shook hands with Dale Sanders, former US spear-fishing champion who has over 50 years of canoeing experience.

I left Hadley at the Memphis Yatch Club and then Dale and I loaded my gear into his car. Dale and his wife Miriam treated me very well while I stayed with them. I met their children, son-in-law and grandkids and felt very welcomed by their family.

I left Memphis Dec. 17 and experienced some windy days, but by Dec. 24 the weather was exceptionally warm and pleasant. That changed radically on the 25th when the worst Christmas Day storm in the history of the region attacked Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana.

Fortunately, I had found a hunting camp as the sun was setting on the 24th. The cabin was on stilts, as are many buildings along the river. I set up my tent under the cabin which was a good 6 to 7 feet above ground. The weather forecast was calling for quarter-sized hail, strong winds and possible tornadoes. A nylon tent offers very meagre shelter from a tornado, but I gambled on a tornado being more likely to rip the roof off the cabin rather than snapping the sturdy timbers the building rested on. I tried not to think what could happen if the structure crashed down on me.

Once the rain started on the 25th, it rained hard for long periods of time. I waited for a lull in the downpour to dig a trench in front of the tent because the rain was pooling on the ground after it ran off the eves. The wind was strong so I tied the tent poles to the stilts and this secured the tent, but it didn't stop the north wind from ballooning the nylon.

I listened to my weather radio with keen interest. The list of Mississippi and Arkansas counties as well as Louisiana parishes under advisories was long, but other than being cold I escaped the storm unscathed. The next day, the radio said 200 000 Mississippi homes were without power and several of the state's counties were in states of emergency. What's more, 34 tornadoes were reported in the tri-state region including an F2 and even an F3 tornado with winds of 140 mph.

The storm cooled the weather considerably. I continued my journey, but the wet and cold days didn't put many smiles on my face. I still wished I could find a rhythm, but in six weeks on the Mississippi the consistency I wanted remained elusive. Although each day was distinct and offered unique weather and diverse challenges, their common thread was that they got me closer to New Orleans. Rhythm or not, I progressed.

On Dec. 30, I arrived at a large, tree-covered island where the three states share borders - Arkansas formed the western boundary, Mississippi was to the east and Louisiana covered the island's southern tip. A satisfied smile lingered as I watched my first Louisiana sunset. The next morning, I left my uncle an offering on the Louisiana border.

I was down to two states. Mississippi would be on the left bank for at least another week, but the final state was on the other side - Louisiana.

Starting Jan. 1, the weather gave me the consistency I had wanted for so long. There was hardly any wind and the sunny, dry days allowed my progress to jump to 25 miles a day.

I enjoyed exploring some bayous along the way.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ll_u7TFADaU

Between the Louisiana border and Baton Rouge, there were only two nights with rain. Although the rain was very heavy one night (Jan 9, 3 inches) the weather cleared quickly the next day. Starting Jan 10, I pushed myself very hard to get to Baton Rouge ahead of a four-day soaker. I covered roughly 100 miles in three days and arrived in Baton Rouge Jan. 13.

The Jan. 9 rainstorm caused lots of debris to run into the river.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qy1AChTOv1U

And that rain caused some flooding.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CcP--h42EU

Once in Baton Rouge, I tried canoeing up a bayou to get me closer to a public library that was located a few miles away from the Mississippi. The bayou was swollen from rain and running white water in some places. I tried my best but I simply could not paddle upstream. I anchored Hadley to the muddy shore and walked towards a livestock auction barn, surprisingly called Dominique's Livestock, where I planned to call a tow truck to move my outfit to a motel. While at the barn, I met Charlie Hurston and he seemed like the type of person who would help a stranger. After the auction, Charlie, his friend Jeffrey and myself loaded my gear into his horse trailer and they drove me to a motel.

While in Baton Rouge, Kyle Peveto, a reporter with The Advocate, interviewed me about Canoe to New Orleans. He was very generous with his time and drove me around Baton Rouge so I could get my GPS fixed. Kyle's kindness was typical of all the people I met in Louisiana.

The confluence is located a few miles north of St. Louis, a city I left Nov. 21, which was the two-year anniversary of M'Nonc Mitch's passing. On the 22nd, I arrived in Crystal City, Missouri where I had planned to get groceries and send a few articles. When I saw the pic-nic shelter at the Plattin Rock Boat Club located along the Mississippi, I knew I found my campsite. Not only did it provide shelter from the rain, but it had power outlets and lights. Having been limited to candles and flashlights for most of the trip, I enjoyed robbing the night of its darkness.

I met several members of the boat club, including Dave Hanley who gave me a replacement paddle for the one I broke on the Missouri River. Dave has helped many paddlers on their way to New Orleans or the Gulf of Mexico.

The Mississippi River was exceptionally low and the current was weak. This was the result of the severe and catastrophic drought that brutalized the mid-west United States that summer and continued into the fall. When planning Canoe to New Orleans, I had expected the current to be much stronger and had hoped to spend Christmas in New Orleans. This was no longer possible. To make matters worse, on Nov. 23 the Army Corps of Engineers greatly reduced the flow from Gavin's Point Dam on the Missouri River. This cheated the Mississippi of water from one of its most important tributaries. The dam restriction weakened the current and caused water levels to free-fall. Some nights, the river would drop one to two feet, to say nothing of daytime drops which are harder to notice.

Because the water was historically low, barges were only loaded to 3/4 capacity and word on the river was that barge traffic between St. Louis and Cairo, Illinois would soon be halted and that all barges would be banned from the entire river Dec. 22. I was told such a closure had never occurred in the history of commercial shipping on the Mississippi. Such were the water levels.

To compound the slow progress because of the anemic current, I was also being delayed by thick morning fog that would linger until noon leaving only four to five hours of light from the short autumn days. The determined south wind further slowed my forward advance. For the last 365 miles on the Missouri, I had gotten into a rhythm and I was used to clear, cold days with strong current that allowed me to consistently paddle 20 to 35 miles a day with a high of 42 miles. During my first week on the Mighty Mississippi, I averaged only a disappointing 13 miles a day.

I was frustrated by the slow progress and I was concerned my trip could take much longer than planned, but I decided to delay worrying until I reached Cairo, which is where the Ohio River, the Mississippi's foremost tributary, would increase the flow, or so I hoped. The Ohio drains Eastern states that weren't impacted by the drought.

On Nov. 25, I stopped in Sainte Genevieve, Missouri. Since high school, I've wondered why so many places in Missouri have French names. I decided to explore one and find out. I toured the Louis Bolduc house where I learned from my tour guide that many French-Canadians came to the area in the 1700s. The economy of the time included farming as well as mining lead and salt. Louis Bolduc was from Quebec. He built his home in 1792 and members of his family lived there until 1948 at which point the house was restored and became a museum. I met a lot of nice people in Ste. Genevieve and this gave me a boost of enthusiasm despite the difficult paddling.

Beyond Ste. Genevieve, the wind co-operated more and I was able to increase my daily average to 20 miles, but in certain locations the river bed was exposed and in some places the Mississippi was too shallow to even float a canoe. Like the barges, I religiously tried to stay in the deepest water.

As you see, barges weren't the only thing I had to share the river with.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Nwu-Er_7TI

I stopped in Cape Girardeau Nov. 30 and asked two women for directions to the grocery store. The elderly woman didn't know and she asked her middle-aged daughter-in-law who in turn asked me if I was on foot. When I said I was, the mother-in-law, Dolores, 82, offered me a ride. Then Daughter-in-Law said, "If you do anything to hurt her I'll get you." I laughed, but knew she was serious. I didn't take offence given the size of my beard and the fact that I smelled like several campfires, "Dolores, you must be a good person," I replied, "Daughters-in-law don't usually care for their mothers-in-law that much."

At the grocery store, we talked about her grandkids, her career as a Grade 6 teacher and my uncle Mitch. While in the produce department, her cell phone rang. I pretended not to listen, but I knew who was calling. "I'm fine," Dolores said, "We're having a wonderful conversation."

On Dec. 3, I reached the Ohio River. The wide expanse of water at the confluence was being churned by strong gusts and during the strongest I was unable to control my canoe. Not wanting to be blown into the path of a barge, I went to shore and set up camp in a stand of dense willows where I waited for morning. Soon, I would know if the Ohio was making the Mississippi flow faster.

The Ohio didn't disappoint me. From the confluence, I made good progress. On Dec. 4, I arrived in Kentucky and on the 5th I was in Tennessee. Passing from Illinois, to Kentucky and then into Tennessee, all in the span of a few days, encouraged me and made me feel like I was making headway.

By Dec. 8, I arrived in Caruthersville, Missouri. I needed a pair of waterproof gloves and went to the sporting goods store. The owner was about 70 and his six-year-old granddaughter was there. She didn't call him grandpa. Instead, she called him "Big Daddy." Her choice of words meant I was getting close to the South. The menu at the restaurant reflected this as well and featured collar greens, country fried steak and corn bread. The people spoke with the long Southern drawl.

Technically, Missouri is considered a Mid-West state, but during the Civil War it was a microcosm of the larger conflict. The northern and southern portions of the state were at war with each other. Missouri is where the transition to the South occurs.

Very heavy rain was in the overnight forecast and I looked for a spot to shelter my canoe, which I had named Hadley, so that it wouldn't fill with rainwater. I found cover under one of the two walkways that extend from shore to a river boat casino named Lady Luck. As I was preparing to drop anchor, a man on the walkway asked where I was from. When I answered Canada, he replied, "Makes sense, there's no hockey this season so there's nothing better to do in Canada." Jeremy Odell is one of the casino managers. He gave me a $20 voucher for the restaurant and $10 cash for drinks.

That night, the rain poured down mightily. And still the river went down, but the next night it began to rise. The current increased and in one narrow spot it propelled me to 10 mph. Although this was only for a few hundred yards, the increase to my morale was huge.

On Dec. 10, I exited Missouri. Tennessee was now on the east bank and Arkansas on the west. I was in the South. The weather improved and it was a pleasure to be on the river.

As I entered Memphis on Dec. 13, I saw a white-bearded man on the bank. He flailed his arm and obviously wanted to get my attention. I looked closer and saw a camera. The bearded stranger must have wanted a picture. Then he cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted, "Are you Dom?" I shouted back I was. "There's a boat ramp over there." He pointed downstream 100 yards.

I was surprised anyone in Memphis knew me. Previous to the trip, I'd never been south of the Great Lakes. However, I suspected I knew the white-bearded stranger's identity. I had heard of him through the paddlers' underground, the network of canoeing and kayaking enthusiasts, but I thought he lived somewhere along the Missouri River.

I eased Hadley into the slack water at the foot of the boat ramp. The Beard snapped a few pictures. I shook hands with Dale Sanders, former US spear-fishing champion who has over 50 years of canoeing experience.

I left Hadley at the Memphis Yatch Club and then Dale and I loaded my gear into his car. Dale and his wife Miriam treated me very well while I stayed with them. I met their children, son-in-law and grandkids and felt very welcomed by their family.

I left Memphis Dec. 17 and experienced some windy days, but by Dec. 24 the weather was exceptionally warm and pleasant. That changed radically on the 25th when the worst Christmas Day storm in the history of the region attacked Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana.

Fortunately, I had found a hunting camp as the sun was setting on the 24th. The cabin was on stilts, as are many buildings along the river. I set up my tent under the cabin which was a good 6 to 7 feet above ground. The weather forecast was calling for quarter-sized hail, strong winds and possible tornadoes. A nylon tent offers very meagre shelter from a tornado, but I gambled on a tornado being more likely to rip the roof off the cabin rather than snapping the sturdy timbers the building rested on. I tried not to think what could happen if the structure crashed down on me.

Once the rain started on the 25th, it rained hard for long periods of time. I waited for a lull in the downpour to dig a trench in front of the tent because the rain was pooling on the ground after it ran off the eves. The wind was strong so I tied the tent poles to the stilts and this secured the tent, but it didn't stop the north wind from ballooning the nylon.

I listened to my weather radio with keen interest. The list of Mississippi and Arkansas counties as well as Louisiana parishes under advisories was long, but other than being cold I escaped the storm unscathed. The next day, the radio said 200 000 Mississippi homes were without power and several of the state's counties were in states of emergency. What's more, 34 tornadoes were reported in the tri-state region including an F2 and even an F3 tornado with winds of 140 mph.

The storm cooled the weather considerably. I continued my journey, but the wet and cold days didn't put many smiles on my face. I still wished I could find a rhythm, but in six weeks on the Mississippi the consistency I wanted remained elusive. Although each day was distinct and offered unique weather and diverse challenges, their common thread was that they got me closer to New Orleans. Rhythm or not, I progressed.

On Dec. 30, I arrived at a large, tree-covered island where the three states share borders - Arkansas formed the western boundary, Mississippi was to the east and Louisiana covered the island's southern tip. A satisfied smile lingered as I watched my first Louisiana sunset. The next morning, I left my uncle an offering on the Louisiana border.

I was down to two states. Mississippi would be on the left bank for at least another week, but the final state was on the other side - Louisiana.

Starting Jan. 1, the weather gave me the consistency I had wanted for so long. There was hardly any wind and the sunny, dry days allowed my progress to jump to 25 miles a day.

I enjoyed exploring some bayous along the way.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ll_u7TFADaU

Between the Louisiana border and Baton Rouge, there were only two nights with rain. Although the rain was very heavy one night (Jan 9, 3 inches) the weather cleared quickly the next day. Starting Jan 10, I pushed myself very hard to get to Baton Rouge ahead of a four-day soaker. I covered roughly 100 miles in three days and arrived in Baton Rouge Jan. 13.

The Jan. 9 rainstorm caused lots of debris to run into the river.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qy1AChTOv1U

And that rain caused some flooding.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CcP--h42EU

Once in Baton Rouge, I tried canoeing up a bayou to get me closer to a public library that was located a few miles away from the Mississippi. The bayou was swollen from rain and running white water in some places. I tried my best but I simply could not paddle upstream. I anchored Hadley to the muddy shore and walked towards a livestock auction barn, surprisingly called Dominique's Livestock, where I planned to call a tow truck to move my outfit to a motel. While at the barn, I met Charlie Hurston and he seemed like the type of person who would help a stranger. After the auction, Charlie, his friend Jeffrey and myself loaded my gear into his horse trailer and they drove me to a motel.

While in Baton Rouge, Kyle Peveto, a reporter with The Advocate, interviewed me about Canoe to New Orleans. He was very generous with his time and drove me around Baton Rouge so I could get my GPS fixed. Kyle's kindness was typical of all the people I met in Louisiana.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After sitting out a four-day rain in a Baton Rouge motel, the weather cleared and on Jan. 18 I returned Hadley to the Mississippi’s water. Kyle drove me to the river where I met his colleague Bill Feig who captured pictures for the article.

Baton Rouge was a transition point. The river bends east past Baton Rouge after following a southerly course since its headwaters over two thousand river miles away in Minnesota. Between Baton Rouge and the Gulf of Mexico 230 river miles away, the Mississippi is plied by giant ocean-going vessels. Ultimately, Baton Rouge marked the beginning of the end. There would be no more stops until New Orleans.

On the 20th, my GPS showed that certain points of land jutting into the river were named after their distance to New Orleans. The first I noticed was 81-Mile Point. After nearly 8 months, the remaining distance was now in double digits.

For the night of the 21st, I camped on the other side of the levee from Oak Alley. Also called the “Grande Dame” of Louisiana’s sugar cane plantations, Oak Alley is known for its spectacular 300-year-old oaks which extend from the antebellum mansion’s front door to the River Road a quarter-mile away. The 28 trees create a canopy and a calm atmosphere.

I enjoyed spending time at Oak Alley. I met the guides and learned about the plantation’s former owners. I also met four Canadian tourists and visited with them.

Several miles east of the plantation, I tuned my weather radio to the local station and heard the electronic voice say sweet words, “Here is the forecast for the New Orleans metropolitan area.” I was getting close! But before completing the final 25 miles to Jackson Square, my arrival point in the French Quarter, I set up camp near Luling, Louisiana and waited for my parents, Ron and Denise, to arrive with my aunt and uncle Annette and Gerry Breton. Like my mom, Annette is Michel’s sister.

The four of them climbed the levee near Luling on the morning of Jan. 26. None of them had seen me since my beard had grown to Al Qaeda-like proportions.

Shortly after their arrival, we were met by a television crew from CBS who flew from New York to film a segment for On the Road, which is a part of the CBS Evening News. Steve Hartman, the host; Miles Doran, the producer, and Bob Caccamise, the cameraman, spent the afternoon working on the segment. We talked about Mitch, his life and death, and the film crew got video of me and my camp.

The next day, Bob filmed from the canoe while Steve and Miles captured video from the riverbank. In the afternoon, my mom and dad as well as my aunt and uncle took turns paddling with me. The first was ma tante Annette (ma tante is French for aunty.) I'm not sure she'd like her age revealed, but there's no harm in saying it was her birthday. Last year, she celebrated by para-sailing in Mexico. This year, she canoed on one of North America's longest rivers. She tells me she doesn't plan to climb Mount Everest next year.

Mon oncle Gerry was next. We came across a huge flock of ducks whose wings buzzed loudly when they took to the air upon our approach. Mon oncle and I pulled and pushed Hadley through willows and burrs to land at the next rendez-vous where Dad had to walk on a fallen tree to get into the canoe. We crashed through the vegetation and returned the canoe to the strong current as it flowed past the industrial landscape of refineries, grain terminals and coal-laden barges.

Once we had canoed to the next meeting spot, Dad left the bow seat and Mom took his place. She canoed with me until 9-Mile Point where we found shelter from the ships' wake behind a moored barge. I looked on shore for a campsite and then the five of us emptied Hadley and pulled him out of the water. We had a shore-lunch of cheese, crackers and wine before mon oncle and Dad set up my camp for me.

My family and the CBS crew returned on the morning of the 28th and we prepared for my arrival at Jackson Square. The remaining distance was down to single digits.

Hadley and I would have Mitch's ashes at Jackson Square in about two hours. With Hadley loaded, I left my final camp and paddled away from 9-Mile Point. My mind wandered to all the hours I spent in the past eight months gazing at my GPS map. I had measured and remeasured the distance to the square countless times. Now I could see New Orleans' skyline. I had to keep my mind focused on paddling. There were massive container ships ahead of me and barges were passing in both directions.

When I rounded the very last bend of Canoe to New Orleans, I was able to see the large steel express-way bridge which crosses the Mississippi. For months, I had visualized myself passing under it in much the same manner as a runner or race car driver crosses the finish line. I aligned Hadley with the exact middle of the span and canoed past my finish line. I was down to one mile.

Then the Coast Guard pulled me over. I'm not sure what the proper maritime term is for getting stopped by law enforcement, but the Coast Guard motored their orange and grey boat next to Hadley and held on to him. Their craft wasn't much longer, but it had a machine gun mounted on the bow.

They asked me for my ID and said the waterfront was a secure zone due to the Super Bowl. The current was very strong and pulling us with speed and vigour. With three-quarters of a mile to go, I didn't want to float to Jackson Square with a Coast Guard agent holding my canoe. I described the project and explained CBS was filming me from under the bridge and from Jackson Square. The agents agreed to meet me on shore if they needed to question me further. With Hadley free from their grasp, I paddled closer to the bank and passed near the paddle wheeler Natchez on top of which is mounted a steam organ that a lady started to play. The first tune was Old Man River. I didn't think she was playing for me, but I began to suspect otherwise when the second song was Row, Row, Row Your Boat.

With only a few hundred yards to go until the wooden steps that descend into the river, I could see a crowd had gathered. They were cheering and waving at me. As I got closer, I could see individual people. Again, I needed to remain vigilant. The current was flowing towards me in a back eddy so I focused on maintaining a steady stroke.

Waves bounced Hadley against the stairs as I tied him to a nearby chain. A band began to play. I stepped out of the canoe and onto the wet stairs. I got hugs from my family and my mom put Mardi Gras beads around my neck. The scene was one of jubilation and excitement and it was all a surprise welcome. Lots of onlookers shook my hand and posed for pictures with me. A harmonica player puffed a Woody Guthrie tune. It was a great end to a 3270-mile river odyssey.

The canoeing was over. Now it was time for the most important part of the journey - spreading my uncle's ashes. We loaded my gear into the CBS rental vehicle and tied Hadley to the roof rack. Miles, Bob and I scouted a location. I chose Lafayette Park and then my family joined us. The five of us stood in a circle and said kind words about M'Nonc. I sprinkled some of his remains on the ground and Dad covered them with a Saskatchewan Roughriders jersey. We talked to M'Nonc and said we missed him and that he made our lives better.

http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-18563_162-57567256/sentimental-journey-canadian-canoes-to-new-orleans-to-honor-uncle/

On Jan. 30, ma tante Annette, Mom and I returned to the wooden stairs and shared M'Nonc's ashes with the river that returned him to the city he loved. Then we washed the ashes off our hands with the river's water. The overtones were of baptism and of entering a church.

Afterwards, we went to a patio near the Natchez and Dad poured each of us a glass of champagne so we could toast Michel. From there, we went to Bourbon Street and partied in the French Quarter - the exuberance, the celebration, the atmosphere, now we knew first-hand why Mitch loved New Orleans!

Baton Rouge was a transition point. The river bends east past Baton Rouge after following a southerly course since its headwaters over two thousand river miles away in Minnesota. Between Baton Rouge and the Gulf of Mexico 230 river miles away, the Mississippi is plied by giant ocean-going vessels. Ultimately, Baton Rouge marked the beginning of the end. There would be no more stops until New Orleans.

On the 20th, my GPS showed that certain points of land jutting into the river were named after their distance to New Orleans. The first I noticed was 81-Mile Point. After nearly 8 months, the remaining distance was now in double digits.

For the night of the 21st, I camped on the other side of the levee from Oak Alley. Also called the “Grande Dame” of Louisiana’s sugar cane plantations, Oak Alley is known for its spectacular 300-year-old oaks which extend from the antebellum mansion’s front door to the River Road a quarter-mile away. The 28 trees create a canopy and a calm atmosphere.

I enjoyed spending time at Oak Alley. I met the guides and learned about the plantation’s former owners. I also met four Canadian tourists and visited with them.

Several miles east of the plantation, I tuned my weather radio to the local station and heard the electronic voice say sweet words, “Here is the forecast for the New Orleans metropolitan area.” I was getting close! But before completing the final 25 miles to Jackson Square, my arrival point in the French Quarter, I set up camp near Luling, Louisiana and waited for my parents, Ron and Denise, to arrive with my aunt and uncle Annette and Gerry Breton. Like my mom, Annette is Michel’s sister.

The four of them climbed the levee near Luling on the morning of Jan. 26. None of them had seen me since my beard had grown to Al Qaeda-like proportions.

Shortly after their arrival, we were met by a television crew from CBS who flew from New York to film a segment for On the Road, which is a part of the CBS Evening News. Steve Hartman, the host; Miles Doran, the producer, and Bob Caccamise, the cameraman, spent the afternoon working on the segment. We talked about Mitch, his life and death, and the film crew got video of me and my camp.

The next day, Bob filmed from the canoe while Steve and Miles captured video from the riverbank. In the afternoon, my mom and dad as well as my aunt and uncle took turns paddling with me. The first was ma tante Annette (ma tante is French for aunty.) I'm not sure she'd like her age revealed, but there's no harm in saying it was her birthday. Last year, she celebrated by para-sailing in Mexico. This year, she canoed on one of North America's longest rivers. She tells me she doesn't plan to climb Mount Everest next year.

Mon oncle Gerry was next. We came across a huge flock of ducks whose wings buzzed loudly when they took to the air upon our approach. Mon oncle and I pulled and pushed Hadley through willows and burrs to land at the next rendez-vous where Dad had to walk on a fallen tree to get into the canoe. We crashed through the vegetation and returned the canoe to the strong current as it flowed past the industrial landscape of refineries, grain terminals and coal-laden barges.

Once we had canoed to the next meeting spot, Dad left the bow seat and Mom took his place. She canoed with me until 9-Mile Point where we found shelter from the ships' wake behind a moored barge. I looked on shore for a campsite and then the five of us emptied Hadley and pulled him out of the water. We had a shore-lunch of cheese, crackers and wine before mon oncle and Dad set up my camp for me.

My family and the CBS crew returned on the morning of the 28th and we prepared for my arrival at Jackson Square. The remaining distance was down to single digits.

Hadley and I would have Mitch's ashes at Jackson Square in about two hours. With Hadley loaded, I left my final camp and paddled away from 9-Mile Point. My mind wandered to all the hours I spent in the past eight months gazing at my GPS map. I had measured and remeasured the distance to the square countless times. Now I could see New Orleans' skyline. I had to keep my mind focused on paddling. There were massive container ships ahead of me and barges were passing in both directions.

When I rounded the very last bend of Canoe to New Orleans, I was able to see the large steel express-way bridge which crosses the Mississippi. For months, I had visualized myself passing under it in much the same manner as a runner or race car driver crosses the finish line. I aligned Hadley with the exact middle of the span and canoed past my finish line. I was down to one mile.

Then the Coast Guard pulled me over. I'm not sure what the proper maritime term is for getting stopped by law enforcement, but the Coast Guard motored their orange and grey boat next to Hadley and held on to him. Their craft wasn't much longer, but it had a machine gun mounted on the bow.

They asked me for my ID and said the waterfront was a secure zone due to the Super Bowl. The current was very strong and pulling us with speed and vigour. With three-quarters of a mile to go, I didn't want to float to Jackson Square with a Coast Guard agent holding my canoe. I described the project and explained CBS was filming me from under the bridge and from Jackson Square. The agents agreed to meet me on shore if they needed to question me further. With Hadley free from their grasp, I paddled closer to the bank and passed near the paddle wheeler Natchez on top of which is mounted a steam organ that a lady started to play. The first tune was Old Man River. I didn't think she was playing for me, but I began to suspect otherwise when the second song was Row, Row, Row Your Boat.

With only a few hundred yards to go until the wooden steps that descend into the river, I could see a crowd had gathered. They were cheering and waving at me. As I got closer, I could see individual people. Again, I needed to remain vigilant. The current was flowing towards me in a back eddy so I focused on maintaining a steady stroke.

Waves bounced Hadley against the stairs as I tied him to a nearby chain. A band began to play. I stepped out of the canoe and onto the wet stairs. I got hugs from my family and my mom put Mardi Gras beads around my neck. The scene was one of jubilation and excitement and it was all a surprise welcome. Lots of onlookers shook my hand and posed for pictures with me. A harmonica player puffed a Woody Guthrie tune. It was a great end to a 3270-mile river odyssey.

The canoeing was over. Now it was time for the most important part of the journey - spreading my uncle's ashes. We loaded my gear into the CBS rental vehicle and tied Hadley to the roof rack. Miles, Bob and I scouted a location. I chose Lafayette Park and then my family joined us. The five of us stood in a circle and said kind words about M'Nonc. I sprinkled some of his remains on the ground and Dad covered them with a Saskatchewan Roughriders jersey. We talked to M'Nonc and said we missed him and that he made our lives better.

http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-18563_162-57567256/sentimental-journey-canadian-canoes-to-new-orleans-to-honor-uncle/

On Jan. 30, ma tante Annette, Mom and I returned to the wooden stairs and shared M'Nonc's ashes with the river that returned him to the city he loved. Then we washed the ashes off our hands with the river's water. The overtones were of baptism and of entering a church.

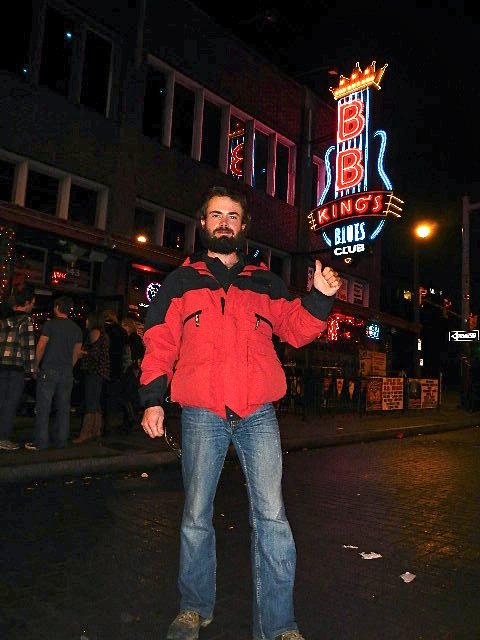

Afterwards, we went to a patio near the Natchez and Dad poured each of us a glass of champagne so we could toast Michel. From there, we went to Bourbon Street and partied in the French Quarter - the exuberance, the celebration, the atmosphere, now we knew first-hand why Mitch loved New Orleans!

|

|

|

I stayed in New Orleans for two weeks after my family left. I experienced the city and discovered its charm. I planned to stay until Mardi Gras and then return to Canada, but before leaving I had a few important tasks to accomplish.

Firstly, I wanted to visit Hadley Castille's grave in Opelousas, Louisiana. Secondly, I needed to find a way to get my canoe home. Most importantly, I wanted to participate in the Krewe of Sainte Anne's procession which allows people to carry the remains of their loved-ones through the French Quarter to the Mississippi River.

Travis and Tyson Holeha flew into New Orleans at the end of the first week of February. I hadn't seen the twins since they took turns canoeing with me at the very start of the journey. We hit New Orleans hard.

We rented an SUV and drove to Hadley's grave in Opelousas. From there, we continued to San Antonio, Texas where we met Marlene Monvoisin. (Her husband Jean-Paul and her son Colton canoed with me on this trip.) She was in San Antonio to deliver two horses and kindly let me put my canoe in her empty horse trailer for the ride back to Saskatchewan. After saying good-bye to Marlene, the Holehas and I returned to New Orleans.

Mardi Gras was Feb. 12 and this was the same day as the Krewe of Sainte Anne's procession. I was very emotional as I walked with Mitch's ashes towards the krewe's meeting point. I cried. I cried a lot. When I arrived, I met Donna Pahl and her friend Deb Hanley along with more of their friends. They were there to honour Deb's husband Buddy Mann, a blues musician. Donna had sent me information about the Krewe of Sainte Anne and invited me to walk with her and her friends. I had expected 50 or so people to participate in the entire procession. I was very wrong. There were hundreds of people, perhaps even thousands and almost all of them wore costumes, some were very elaborate.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La_JvbsoLQM

We marched towards the French Quarter. I was thankful to have been with Donna, Deb and their friends, but I was very distracted, emotional and sullen. My mood improved as we neared Jackson Square because the procession was headed to the same wooden stairs where my canoe trip ended. I felt that was a fitting coincidence.

As I stood on the wooden stairs listening to people weep, I tried to breathe deeply and maintain my composure. I couldn't. I thought about my uncle, knelt by the water, sprinkled his ashes and said, "Bye M'Nonc, merci pour tout pis je vais jamais t'oublier." (Bye M'Nonc, thanks for everything and I'll never forget you.) Canoe to New Orleans was over.

After mourners tearfully spread their loved-one's ashes in the Mississippi, musicians transformed the atmosphere from a remembrance of death to a celebration of life.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSTRqE974Go

That night, Tyson, Travis and I went on a spree in the French Quarter to celebrate Mardi Gras and the successful completion of the journey. We partied until the sun rose and beyond. It's always the boys from Saskatchewan who shut a party down.

The Holehas left that day and I left the day after. I took the train to Glasgow, Montana and my cousin Danielle Hamon met me at the station. We drove north.

Firstly, I wanted to visit Hadley Castille's grave in Opelousas, Louisiana. Secondly, I needed to find a way to get my canoe home. Most importantly, I wanted to participate in the Krewe of Sainte Anne's procession which allows people to carry the remains of their loved-ones through the French Quarter to the Mississippi River.

Travis and Tyson Holeha flew into New Orleans at the end of the first week of February. I hadn't seen the twins since they took turns canoeing with me at the very start of the journey. We hit New Orleans hard.

We rented an SUV and drove to Hadley's grave in Opelousas. From there, we continued to San Antonio, Texas where we met Marlene Monvoisin. (Her husband Jean-Paul and her son Colton canoed with me on this trip.) She was in San Antonio to deliver two horses and kindly let me put my canoe in her empty horse trailer for the ride back to Saskatchewan. After saying good-bye to Marlene, the Holehas and I returned to New Orleans.

Mardi Gras was Feb. 12 and this was the same day as the Krewe of Sainte Anne's procession. I was very emotional as I walked with Mitch's ashes towards the krewe's meeting point. I cried. I cried a lot. When I arrived, I met Donna Pahl and her friend Deb Hanley along with more of their friends. They were there to honour Deb's husband Buddy Mann, a blues musician. Donna had sent me information about the Krewe of Sainte Anne and invited me to walk with her and her friends. I had expected 50 or so people to participate in the entire procession. I was very wrong. There were hundreds of people, perhaps even thousands and almost all of them wore costumes, some were very elaborate.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La_JvbsoLQM

We marched towards the French Quarter. I was thankful to have been with Donna, Deb and their friends, but I was very distracted, emotional and sullen. My mood improved as we neared Jackson Square because the procession was headed to the same wooden stairs where my canoe trip ended. I felt that was a fitting coincidence.

As I stood on the wooden stairs listening to people weep, I tried to breathe deeply and maintain my composure. I couldn't. I thought about my uncle, knelt by the water, sprinkled his ashes and said, "Bye M'Nonc, merci pour tout pis je vais jamais t'oublier." (Bye M'Nonc, thanks for everything and I'll never forget you.) Canoe to New Orleans was over.

After mourners tearfully spread their loved-one's ashes in the Mississippi, musicians transformed the atmosphere from a remembrance of death to a celebration of life.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSTRqE974Go

That night, Tyson, Travis and I went on a spree in the French Quarter to celebrate Mardi Gras and the successful completion of the journey. We partied until the sun rose and beyond. It's always the boys from Saskatchewan who shut a party down.

The Holehas left that day and I left the day after. I took the train to Glasgow, Montana and my cousin Danielle Hamon met me at the station. We drove north.

|

|

|