Part 1. Saskatchewan to St. Louis, the first 2215 miles

The journey began June 8 in Eastend with a great send-off by members of the community along with family and friends.

The first part of the trip was from Eastend to Val Marie. The 180-river-mile

trip took 7 days. I was joined by Tyson Holeha and we made great time, but were challenged by cold temperatures and two days of incessant rain. The positive element was that the rain kept the shallow Frenchman River running high so we were able to go over lots of rock crossings, but there were still dozens of times when we had to get out of my Clipper Prospector to haul it over gravel and sharp stones that were barely covered by mere inches of water. We ran a lot of rapids and riffles and were usually able to get through, but not without a few battle scars to the underside of the canoe.

Click on the pictures to make them bigger. You can also click on the links to videos.

The first part of the trip was from Eastend to Val Marie. The 180-river-mile

trip took 7 days. I was joined by Tyson Holeha and we made great time, but were challenged by cold temperatures and two days of incessant rain. The positive element was that the rain kept the shallow Frenchman River running high so we were able to go over lots of rock crossings, but there were still dozens of times when we had to get out of my Clipper Prospector to haul it over gravel and sharp stones that were barely covered by mere inches of water. We ran a lot of rapids and riffles and were usually able to get through, but not without a few battle scars to the underside of the canoe.

Click on the pictures to make them bigger. You can also click on the links to videos.

|

|

Jean-Paul Monvoisin grew up with my uncle Mitch and lived on the neighbouring farm. Jean-Paul and I left Val Marie June 20. It was great to share stories about M'Nonc and the good old days when he was still with us. The weather was mostly good for our trip, but the mosquitoes were vicious on a few occasions. One of JP's friends named our part of the journey Two Frenchmen on the Frenchman.

|

|

Jean-Paul canoed with me up to the Walker Ranch and after he left I paddled solo for the first time on the trip. At the end of a very windy day (June 24th), I arrived at the border and camped in Canada one last time. The next morning, I heard someone yell, "Hey!" Keep in mind I was in the middle of nowhere and I was surprised to say the least. It was Travis Holeha. He had climbed a hill on the Montana side of the border to get cell coverage. He wanted to text me to get my location. When he crested the hill, he saw my camp. I canoed under the border fence into Montana and met Travis at a crossing where he left his vehicle. Within minutes, we were chatting with a border guard who claimed to have been on patrol, but much more likely had been tipped off. Once I showed him my permit everything was cool. Travis and I completed the rest of the Frenchman and met his parents, Gay and Elpha, at Bjornberg Bridge on the Milk River. Travis returned to Canada with his parents and I continued on my own.

|

|

Paddling the Milk River

On July 5, Marlene and Josee Monvoisin dropped off Colton at Hinsdale, Montana. Colton Monvoisin canoed with me to Glasgow. The mercury soared up to 35 C/95 F and the gnats swarmed us on many occasions, but the trip went well and by July 8 we reached our destination. Colton and I were amazed by the number of Asian carp we saw. Colton was able to snag a carp, as he explains in this video.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qwqLXu_4I4&feature=plcp

We stopped under the bridge near the ghost town of Tampico to see if something I left myself at Easter was still there.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shz36K_t0N0&feature=plcp

The day after Colton and I arrived in Glasgow, Marlene and Josee returned from Josee's horse competition and the three Monvoisins drove back to their farm near Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qwqLXu_4I4&feature=plcp

We stopped under the bridge near the ghost town of Tampico to see if something I left myself at Easter was still there.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shz36K_t0N0&feature=plcp

The day after Colton and I arrived in Glasgow, Marlene and Josee returned from Josee's horse competition and the three Monvoisins drove back to their farm near Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan.

On July 10, my parents met me in Glasgow. My aunt Alyce and cousin Chantal were with them. We spent a few days together before my aunt and cousin returned to Canada. My parents took turns canoeing with me on the Milk River. They alternated days over a period of four days. The weather co-operated for the most part, but on Dad's last day it was very windy. On the last evening, we were invited to supper at the Rorvik Farm and had a great time with them. The next day, my parents had to go back to Saskatchewan, but before they left we spread some of M'Nonc's ashes along the Milk River because he would have really liked all the nice people we met who live along its banks.

I said good-bye to Mom & Dad and canoed to the confluence of the Milk and Missouri Rivers.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_A5ZrNe_EI&feature=plcp

The Muddy Missouri River

After completing the Milk River, I proceeded solo on the Missouri River through the Fort Peck Indian Reservation and experienced some very hot days, but found relief by dunking my clothes in the cold Missouri. The above average heat challenged me on several days during the third week in July, but by the fourth week the weather had returned to seasonal temperatures.

I didn't see very many people along this stretch of the river. In fact, I easily saw more horses than humans.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1x0jdlGMrY&feature=plcp

The landscape from the confluence across the Montana/North Dakota border and to the city of Williston, which I reached July 29, varied from jagged hills cut by erosion to stark badlands to dense cottonwoods and willows.

I said good-bye to Mom & Dad and canoed to the confluence of the Milk and Missouri Rivers.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_A5ZrNe_EI&feature=plcp

The Muddy Missouri River

After completing the Milk River, I proceeded solo on the Missouri River through the Fort Peck Indian Reservation and experienced some very hot days, but found relief by dunking my clothes in the cold Missouri. The above average heat challenged me on several days during the third week in July, but by the fourth week the weather had returned to seasonal temperatures.

I didn't see very many people along this stretch of the river. In fact, I easily saw more horses than humans.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1x0jdlGMrY&feature=plcp

The landscape from the confluence across the Montana/North Dakota border and to the city of Williston, which I reached July 29, varied from jagged hills cut by erosion to stark badlands to dense cottonwoods and willows.

|

|

|

It was bound to happen and it did. My GPS gave me bad directions. It showed a 400-foot-wide channel of the Missouri River that would have allowed me to canoe close to Williston, North Dakota where I could get supplies. The channel turned out to be 10 feet wide with foul, stagnant water. After 100 yards it became a ditch of mud. I'm guessing the GPS was loaded with information taken during the historic flood of 2011.

I decided to walk, but didn't want to leave my equipment out in the open. I pulled my canoe into the abundant growth of willows along the water. Then I hid my canoe and all my gear under a thick blanket of willow branches that I had cut. I saved one of the branches to use as a broom and swept the sand of my tracks.

It would be impossible for me to exaggerate how thick the willows were on my 5-hour walk into Williston. In some spots, the dead willows formed a chain-link fence of intertwined branches I couldn't pass or push through no matter how hard I tried. It was like being in a jungle. I lost confidence in my GPS and navigated by climbing trees, choosing landmarks and working towards them. The willows and mud flats often forced me to backtrack or approach from another direction. Progress was very slow, but to stay positive and focused I kept reminding myself that every step forward was getting me closer to Williston.

The date was July 30th and I discovered a city in the throes of an oil boom, which tends to only be seen as a good thing, but there are many dark elements as well. One of them is that the price of everything is exaggerated. For example, a motel room in Saco, Montana cost me $35. In Williston, expect to pay between $125-$150, if there's vacancy, but probably not. I couldn't afford the room, but didn't have anywhere else to stay. I got the hotel room for the night and then it was cheaper for me to sleep in a rental car.

I spent the next few days updating my website, working on articles, getting supplies and looking for someone with a boat who could get me back to mine. Laden with supplies, walking back through the willow swamp wasn't an option. I felt monetarily trapped in the city. Everything was expensive, but I had to stay until I found a ride out.

I followed a lot of leads. One of them was at a sporting goods store slash gas station slash liquor shop. It was a likely place to find someone with a boat, but no one on staff could help. As I left the store and was walking back to my rental car slash hotel room, I saw someone putting gas in a boat. The craft showed the battle scars of many a day fishing for walleye. I could tell the owner would be an outdoorsman.

That's when I met Nick Gessell and his cousin Brent. Nick once spent several days trapped on an island in a Minnesota Lake. Several of the people in his group had been injured during a tornado. The weather remained unpredictable and threatening so boating to safety was too dangerous. He understood my situation and I later found out that despite his young age, 27, Nick had experienced a heart attack. He also had a long family history of cardiac troubles and had made the changes in his life that will keep him healthy. I was inspired by his story.

We loaded his johnboat with my supplies and cruised toward the willows that concealed my canoe. The current and the electric motor aided our descent of the Missouri River. When we got to my stash, I asked Nick if he could see the canoe. He scanned the willows, but couldn't see my boat. I was proud of the job I had done to hide it, but the canoe hadn't escaped detection. A bull moose had walked by and left his gigantic hoof prints in the sand and mud. Nick made plans to hunt the area in the fall.

We had left Nick's truck further ahead at an irrigation pump. We boated towards the vehicle and made plans to go fishing in Minnesota some day. When we got to the 4 X 4, I helped Nick load his johnboat into the box as the sun disappeared under the horizon.

I thanked Nick for all his help, which had involved no small effort on his part, and watched the headlights bounce across the trail as the aluminum johnboat rattled against the truck's metal box.

The next day, August 3rd, I canoed the remaining portion of the Missouri River before it becomes Lake Sakakawea, which is a 178-mile reservoir that was created by the construction of Garrison Dam. That night, I camped under a hill that gave me a view of the Missouri's willow groves and mud flats as well as a view of the open water of Lake Sakakawea.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwB9xkVjKy4&feature=plcp

The morning brought a strong winds that prevented me from getting on the water. This was to be the theme for the next 14 days: wind. Headwinds delayed my progress considerably, but I reminded myself that despite the low mileage, I was chipping away at the distance between me and Garrison Dam. Waves turn rocks into sand not with force, but with persistence.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5-UQBvyNjo&feature=plcp

Crossing Lake Sakakawea become a routine of fighting the wind, eating huge amounts of food to stay energized, watching every wave with the scrutiny I reserve for mean dogs and erecting my tent in locations that sheltered me from gusts of wind. By August 18, I had crossed Garrison Dam and was back on the free-flowing Missouri River. Having the current to help me was like reuniting with an old friend.

And yet, I'm thankful for Lake Sakakawea's tests and obstacles because overcoming them boosted my confidence for Lake Oahe, which is 50 miles longer and has even greater notoriety for wind and will most likely be one of the most, if not the most, difficult part of the journey.

I decided to walk, but didn't want to leave my equipment out in the open. I pulled my canoe into the abundant growth of willows along the water. Then I hid my canoe and all my gear under a thick blanket of willow branches that I had cut. I saved one of the branches to use as a broom and swept the sand of my tracks.

It would be impossible for me to exaggerate how thick the willows were on my 5-hour walk into Williston. In some spots, the dead willows formed a chain-link fence of intertwined branches I couldn't pass or push through no matter how hard I tried. It was like being in a jungle. I lost confidence in my GPS and navigated by climbing trees, choosing landmarks and working towards them. The willows and mud flats often forced me to backtrack or approach from another direction. Progress was very slow, but to stay positive and focused I kept reminding myself that every step forward was getting me closer to Williston.

The date was July 30th and I discovered a city in the throes of an oil boom, which tends to only be seen as a good thing, but there are many dark elements as well. One of them is that the price of everything is exaggerated. For example, a motel room in Saco, Montana cost me $35. In Williston, expect to pay between $125-$150, if there's vacancy, but probably not. I couldn't afford the room, but didn't have anywhere else to stay. I got the hotel room for the night and then it was cheaper for me to sleep in a rental car.

I spent the next few days updating my website, working on articles, getting supplies and looking for someone with a boat who could get me back to mine. Laden with supplies, walking back through the willow swamp wasn't an option. I felt monetarily trapped in the city. Everything was expensive, but I had to stay until I found a ride out.

I followed a lot of leads. One of them was at a sporting goods store slash gas station slash liquor shop. It was a likely place to find someone with a boat, but no one on staff could help. As I left the store and was walking back to my rental car slash hotel room, I saw someone putting gas in a boat. The craft showed the battle scars of many a day fishing for walleye. I could tell the owner would be an outdoorsman.

That's when I met Nick Gessell and his cousin Brent. Nick once spent several days trapped on an island in a Minnesota Lake. Several of the people in his group had been injured during a tornado. The weather remained unpredictable and threatening so boating to safety was too dangerous. He understood my situation and I later found out that despite his young age, 27, Nick had experienced a heart attack. He also had a long family history of cardiac troubles and had made the changes in his life that will keep him healthy. I was inspired by his story.

We loaded his johnboat with my supplies and cruised toward the willows that concealed my canoe. The current and the electric motor aided our descent of the Missouri River. When we got to my stash, I asked Nick if he could see the canoe. He scanned the willows, but couldn't see my boat. I was proud of the job I had done to hide it, but the canoe hadn't escaped detection. A bull moose had walked by and left his gigantic hoof prints in the sand and mud. Nick made plans to hunt the area in the fall.

We had left Nick's truck further ahead at an irrigation pump. We boated towards the vehicle and made plans to go fishing in Minnesota some day. When we got to the 4 X 4, I helped Nick load his johnboat into the box as the sun disappeared under the horizon.

I thanked Nick for all his help, which had involved no small effort on his part, and watched the headlights bounce across the trail as the aluminum johnboat rattled against the truck's metal box.

The next day, August 3rd, I canoed the remaining portion of the Missouri River before it becomes Lake Sakakawea, which is a 178-mile reservoir that was created by the construction of Garrison Dam. That night, I camped under a hill that gave me a view of the Missouri's willow groves and mud flats as well as a view of the open water of Lake Sakakawea.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwB9xkVjKy4&feature=plcp

The morning brought a strong winds that prevented me from getting on the water. This was to be the theme for the next 14 days: wind. Headwinds delayed my progress considerably, but I reminded myself that despite the low mileage, I was chipping away at the distance between me and Garrison Dam. Waves turn rocks into sand not with force, but with persistence.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5-UQBvyNjo&feature=plcp

Crossing Lake Sakakawea become a routine of fighting the wind, eating huge amounts of food to stay energized, watching every wave with the scrutiny I reserve for mean dogs and erecting my tent in locations that sheltered me from gusts of wind. By August 18, I had crossed Garrison Dam and was back on the free-flowing Missouri River. Having the current to help me was like reuniting with an old friend.

And yet, I'm thankful for Lake Sakakawea's tests and obstacles because overcoming them boosted my confidence for Lake Oahe, which is 50 miles longer and has even greater notoriety for wind and will most likely be one of the most, if not the most, difficult part of the journey.

Canoeing Lake Sakakawea was often miserable. However, entire days spent fighting headwinds were rewarded with beautiful skies in the evening. I've never been anywhere that so consistently ends its days with such amazing sunsets. Trying to describe them with words would insult their beauty.

August 20 was a great day for two reasons. First, I broke my personal best for distance and paddled 30 miles. Second, I met my cousin Chantal Hamon in Bismarck, North Dakota.

We met at the close of the day at a boat ramp on the edge of the beautiful city. The river plays an important part of life in the North Dakotan capital. There were many boaters cruising the water and the homes that line the banks almost invariably have docks to which all manner of fishing boats, pontoon boats and jet skis are moored.

Someone once said a "No Trespassing" sign is like an invitation to a Hamon. That would also apply to "No Camping" signs. Chantal and I read one and then chose to ignore it. We camped on the shore in the city because it was 9:30 at night and too late to paddle to the marina where I hoped to leave my canoe for a few days. No one seemed to mind our tents. Quite a few people hung out on the sandy shore until 11.

The next morning, I paddled to the marina while Chantal checked into a hotel. We met at the marina and loaded my gear into her rental car. For the next two days, Chantal and I worked towards preparing our departure. She typed the press release and articles I had written by hand before she arrived. She also dropped off my dry cleaning, did my laundry and got our groceries while I updated the website, responded to media requests and emails as well as arranged for someone to pick her up in a few days and drive her back to Bismarck.

It was comforting to talk with a person I've known forever. While I've met no shortage of nice people on my trip, the last familiar faces I'd seen were my parents' in the middle of July.

Chantal and I got on the Missouri River August 23. The current was strong and the sun was hot like a summer sun should be, but even in the two days I spent off the river the leaves had lost some of their green.

We made great progress. Having another paddler increases the range and speed significantly. The first night, we camped in a cottonwood grove that had seen a grass fire several years ago. Some of the trees still had charred bark which contrasted against the vibrant yellow sunflowers and goldenrods.

The second day was more challenging due to large waves and strong winds. There was a 20-foot gap extending from the shore where the waves weren't as big. We tried to remain in that safer zone, but the wind would occasionally push us from our relative safety into the path of the rolling waves, some of which were the largest to date.

The wind gathered intensity during the afternoon and at times I couldn't hear what Chantal was saying even though she was only 10 feet away. By early evening, the wind had become fierce and on two or three occasions spun the canoe despite the weight of the gear and the occupants' efforts to right the craft. Clearly, it was no longer safe to be on the water. There were also thunder clouds charging us from behind dragging a steel-blue blanket of rain.

When the Hazelton boat ramp appeared, we jettisoned the day's goal of getting to the Fort Rice boat ramp and crossed the Missouri at a narrow section protected from the wind by high cliffs. We tied the canoe to the dock and set up our tents behind three huge spruce trees that did an excellent job sheltering us from rain and wind. While hauling gear to the camp, we were struck by two very hard blasts of wind that exceeded 40 mph.

And the morning was beautiful. Chantal and I made a shrine to M'Nonc on the beach.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBIlKKNQtUs&feature=plcp

We canoed just over two miles to Fort Rice and met Bill Butcher and his sailing buddy Rick Robinson. I got Bill's name from The Complete Paddler, a guide book to the Missouri River written by David Miller. Bill enjoys sailing and spends his weekends on Lake Sakakawea with his wife Dina. Rick enjoys refurbishing sail boats and has even built his own. We chatted for a bit and then they drove Chantal back to her rental car at the marina.

I continued by myself towards Lake Oahe. Maps show it begins at Bismarck, but to me a lake doesn't have current so I was on the Missouri River. I would say the current slips away where the Cannonball River enters the lake. The flowing water offers so little discharge as to be nearly imperceptible. Just north of the Cannonball's mouth is a 60-foot high sandstone cliff that extends a quarter-mile along the water's edge. It is home to thousands of swallows who've chiseled countless nests into the cliff face. The scale and volume is worthy of the descriptions of unfathomable numbers of animals left to us by the early Western explorers.

But this wasn't a strictly Western landscape. There were signs of the East such as oak trees that I camped under on the opposite shore. At times, the 100th meridian is cited as the division between East and West and as a general rule Lake Oahe runs from north to south at 100.80 degrees. It is on a border of sorts, but one that doesn't consider regional variations in climate, vegetation and topography.

The wind would generally blow from the south and south-east, but then shift to the north and north-west after thunderstorms or windstorms. Rarely, or perhaps never, will you hear a Canadian say he's thankful for the north wind, but in this case the northers weren't cold. They were helpful to me and I took advantage of them at every instance and frequently rode the wind until 3 or 4 in the morning.

When the wind is from the right direction, I use a sail. Imagine a hula-hoop that's five feet across and covered in blue nylon. It attaches to the front of my canoe, but because of its size it would obstruct my vision if it wasn't for a clear plastic window sewn into the middle. There are two reins to help steer, one on each side.

My average paddling speed on a lake is 2.5 mph, but with the sail I can cruise at 4 to 5 mph. This might not sound like a big difference, but if you compare it to highway travelling it would be like increasing your speed from 60 to 120 mph.

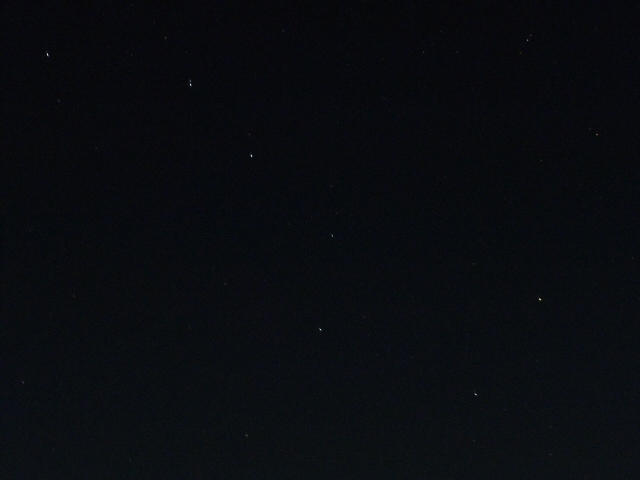

The sail, the moonlight and the northwest wind were the elements that allowed me to cover half of Oahe's 230 miles. The nights of August 28 and 29 were clear and illuminated by the nearly full moon. The 29th was exceptional sailing weather. The daytime heat of 106 F or 43 C broke the old record from 1961 and kept night temperatures warm, even hot. I wore a T-shirt until 2:30, but then changed into a long-sleeved shirt not because I usually find 75 F cool, but it felt that way after 106.

The wind blew hard and I stayed close to the shore. I often startling fish at the surface who splashed and thrashed a few feet away from my canoe. I was in a black and white world. The moon light was bright enough to cast shadows, but colours fused into monochromatic shades of grey, black and blacker.

I went to shore at 4 am and searched for a sheltered spot to protect me from gusts. As I approached some stunted ash trees, I saw a creature foraging on the beach. The bright white stripes along its jet black body alerted me not to get too close or I might smell funky for days. I got up at 8 am and continued to harness the robust Oahe breeze until 2:30 pm at which point I arrived at Mobridge, South Dakota - the halfway point between the start and finish of Lake Oahe.

While in Mobridge, I met Bob Klein. He's a retired teacher who worked in Saudi Arabia for 28 years. He speaks Arabic, some Lakota and has travelled to amazing places like Iran, Lebanon and Sri Lanka, which he prefers to call Ceylon. Bob was a big help and toured me around the area and drove me to get supplies.

From Mobridge to Whitlock I sailed mostly at night to avoid the desiccating wind. Always the wind. It's the dominant feature in a landscape barren. The shore - rocks. The hills - void of grass. The animals - few in number and variety. Always the wind.

The pattern of travelling at night and cursing the wind during the day continued until Sept. 7. I arrived at Little Bend Peninsula and stayed overnight. The next day I executed a portage over the peninsula.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XvDCExcHncc&feature=plcp

The portage put the wind at my back and allowed my to make almost 28 miles. My goal was to reach Oahe Dam without stopping, a distance of over 35 miles. I canoed until midnight and then cooked supper as I waited for the quarter moon to rise in the east and illuminate the lake. The lunar glow rippled on the placid water, but by 4 in the morning the low temperatures and frost warning had me shivering despite several layers of clothing and my life jacket so I found a sheltered bay and slept for a few hours in a warm sleeping bag.

The last day on Lake Oahe reminded me why I had canoed at night. It was hell. Thirty-mile-an-hour-headwind hell, but I had decided Sept. 9 was to be my last day on the meanest of the Missouri reservoirs - no matter what.

I stayed close to the shore so to avoid the waves, but crossing bays left me exposed to La Vieille, which is what the French-Canadian fur trappers and voyageurs called the wind. La Vieille literally means old woman, but it has an added meaning and is used to describe a miserable old hag. I understand their need to personify the wind - it makes hating it easier. I'm also sure they used term La Vieille in a long string of religiously-themed cuss words for which the old time French-Canadians were well-known. I preserved the tradition.

I texted Patrick Wellner when I got to Oahe Dam. He had heard of Canoe to New Orleans through Norm Miller's Facebook site called Missouri River Paddlers. Patrick and I loaded my outfit into his truck and he drove me to the campsite at the foot of the dam where I could see the Missouri River running strong towards Pierre, South Dakota. I proceeded to the state capital the next day and spent some time resting and preparing my passage through Lake Sharpe, the third of five lakes on my route.

While in Pierre, I found nuthatch on the sidewalk. The bird let me pick it up.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_ZwD0n4esk&feature=plcp

We met at the close of the day at a boat ramp on the edge of the beautiful city. The river plays an important part of life in the North Dakotan capital. There were many boaters cruising the water and the homes that line the banks almost invariably have docks to which all manner of fishing boats, pontoon boats and jet skis are moored.

Someone once said a "No Trespassing" sign is like an invitation to a Hamon. That would also apply to "No Camping" signs. Chantal and I read one and then chose to ignore it. We camped on the shore in the city because it was 9:30 at night and too late to paddle to the marina where I hoped to leave my canoe for a few days. No one seemed to mind our tents. Quite a few people hung out on the sandy shore until 11.

The next morning, I paddled to the marina while Chantal checked into a hotel. We met at the marina and loaded my gear into her rental car. For the next two days, Chantal and I worked towards preparing our departure. She typed the press release and articles I had written by hand before she arrived. She also dropped off my dry cleaning, did my laundry and got our groceries while I updated the website, responded to media requests and emails as well as arranged for someone to pick her up in a few days and drive her back to Bismarck.

It was comforting to talk with a person I've known forever. While I've met no shortage of nice people on my trip, the last familiar faces I'd seen were my parents' in the middle of July.

Chantal and I got on the Missouri River August 23. The current was strong and the sun was hot like a summer sun should be, but even in the two days I spent off the river the leaves had lost some of their green.

We made great progress. Having another paddler increases the range and speed significantly. The first night, we camped in a cottonwood grove that had seen a grass fire several years ago. Some of the trees still had charred bark which contrasted against the vibrant yellow sunflowers and goldenrods.

The second day was more challenging due to large waves and strong winds. There was a 20-foot gap extending from the shore where the waves weren't as big. We tried to remain in that safer zone, but the wind would occasionally push us from our relative safety into the path of the rolling waves, some of which were the largest to date.

The wind gathered intensity during the afternoon and at times I couldn't hear what Chantal was saying even though she was only 10 feet away. By early evening, the wind had become fierce and on two or three occasions spun the canoe despite the weight of the gear and the occupants' efforts to right the craft. Clearly, it was no longer safe to be on the water. There were also thunder clouds charging us from behind dragging a steel-blue blanket of rain.

When the Hazelton boat ramp appeared, we jettisoned the day's goal of getting to the Fort Rice boat ramp and crossed the Missouri at a narrow section protected from the wind by high cliffs. We tied the canoe to the dock and set up our tents behind three huge spruce trees that did an excellent job sheltering us from rain and wind. While hauling gear to the camp, we were struck by two very hard blasts of wind that exceeded 40 mph.

And the morning was beautiful. Chantal and I made a shrine to M'Nonc on the beach.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBIlKKNQtUs&feature=plcp

We canoed just over two miles to Fort Rice and met Bill Butcher and his sailing buddy Rick Robinson. I got Bill's name from The Complete Paddler, a guide book to the Missouri River written by David Miller. Bill enjoys sailing and spends his weekends on Lake Sakakawea with his wife Dina. Rick enjoys refurbishing sail boats and has even built his own. We chatted for a bit and then they drove Chantal back to her rental car at the marina.

I continued by myself towards Lake Oahe. Maps show it begins at Bismarck, but to me a lake doesn't have current so I was on the Missouri River. I would say the current slips away where the Cannonball River enters the lake. The flowing water offers so little discharge as to be nearly imperceptible. Just north of the Cannonball's mouth is a 60-foot high sandstone cliff that extends a quarter-mile along the water's edge. It is home to thousands of swallows who've chiseled countless nests into the cliff face. The scale and volume is worthy of the descriptions of unfathomable numbers of animals left to us by the early Western explorers.

But this wasn't a strictly Western landscape. There were signs of the East such as oak trees that I camped under on the opposite shore. At times, the 100th meridian is cited as the division between East and West and as a general rule Lake Oahe runs from north to south at 100.80 degrees. It is on a border of sorts, but one that doesn't consider regional variations in climate, vegetation and topography.

The wind would generally blow from the south and south-east, but then shift to the north and north-west after thunderstorms or windstorms. Rarely, or perhaps never, will you hear a Canadian say he's thankful for the north wind, but in this case the northers weren't cold. They were helpful to me and I took advantage of them at every instance and frequently rode the wind until 3 or 4 in the morning.

When the wind is from the right direction, I use a sail. Imagine a hula-hoop that's five feet across and covered in blue nylon. It attaches to the front of my canoe, but because of its size it would obstruct my vision if it wasn't for a clear plastic window sewn into the middle. There are two reins to help steer, one on each side.

My average paddling speed on a lake is 2.5 mph, but with the sail I can cruise at 4 to 5 mph. This might not sound like a big difference, but if you compare it to highway travelling it would be like increasing your speed from 60 to 120 mph.

The sail, the moonlight and the northwest wind were the elements that allowed me to cover half of Oahe's 230 miles. The nights of August 28 and 29 were clear and illuminated by the nearly full moon. The 29th was exceptional sailing weather. The daytime heat of 106 F or 43 C broke the old record from 1961 and kept night temperatures warm, even hot. I wore a T-shirt until 2:30, but then changed into a long-sleeved shirt not because I usually find 75 F cool, but it felt that way after 106.

The wind blew hard and I stayed close to the shore. I often startling fish at the surface who splashed and thrashed a few feet away from my canoe. I was in a black and white world. The moon light was bright enough to cast shadows, but colours fused into monochromatic shades of grey, black and blacker.

I went to shore at 4 am and searched for a sheltered spot to protect me from gusts. As I approached some stunted ash trees, I saw a creature foraging on the beach. The bright white stripes along its jet black body alerted me not to get too close or I might smell funky for days. I got up at 8 am and continued to harness the robust Oahe breeze until 2:30 pm at which point I arrived at Mobridge, South Dakota - the halfway point between the start and finish of Lake Oahe.

While in Mobridge, I met Bob Klein. He's a retired teacher who worked in Saudi Arabia for 28 years. He speaks Arabic, some Lakota and has travelled to amazing places like Iran, Lebanon and Sri Lanka, which he prefers to call Ceylon. Bob was a big help and toured me around the area and drove me to get supplies.

From Mobridge to Whitlock I sailed mostly at night to avoid the desiccating wind. Always the wind. It's the dominant feature in a landscape barren. The shore - rocks. The hills - void of grass. The animals - few in number and variety. Always the wind.

The pattern of travelling at night and cursing the wind during the day continued until Sept. 7. I arrived at Little Bend Peninsula and stayed overnight. The next day I executed a portage over the peninsula.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XvDCExcHncc&feature=plcp

The portage put the wind at my back and allowed my to make almost 28 miles. My goal was to reach Oahe Dam without stopping, a distance of over 35 miles. I canoed until midnight and then cooked supper as I waited for the quarter moon to rise in the east and illuminate the lake. The lunar glow rippled on the placid water, but by 4 in the morning the low temperatures and frost warning had me shivering despite several layers of clothing and my life jacket so I found a sheltered bay and slept for a few hours in a warm sleeping bag.

The last day on Lake Oahe reminded me why I had canoed at night. It was hell. Thirty-mile-an-hour-headwind hell, but I had decided Sept. 9 was to be my last day on the meanest of the Missouri reservoirs - no matter what.

I stayed close to the shore so to avoid the waves, but crossing bays left me exposed to La Vieille, which is what the French-Canadian fur trappers and voyageurs called the wind. La Vieille literally means old woman, but it has an added meaning and is used to describe a miserable old hag. I understand their need to personify the wind - it makes hating it easier. I'm also sure they used term La Vieille in a long string of religiously-themed cuss words for which the old time French-Canadians were well-known. I preserved the tradition.

I texted Patrick Wellner when I got to Oahe Dam. He had heard of Canoe to New Orleans through Norm Miller's Facebook site called Missouri River Paddlers. Patrick and I loaded my outfit into his truck and he drove me to the campsite at the foot of the dam where I could see the Missouri River running strong towards Pierre, South Dakota. I proceeded to the state capital the next day and spent some time resting and preparing my passage through Lake Sharpe, the third of five lakes on my route.

While in Pierre, I found nuthatch on the sidewalk. The bird let me pick it up.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_ZwD0n4esk&feature=plcp

|

|

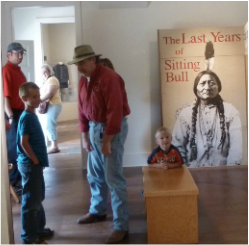

Bob Klein drove me to Sitting Bull's grave which overlooks Mobridge, South Dakota. He also dropped my groceries off near the water and entertained me with stories about hunting in Kenya, Ethiopia, Alaska and Afghanistan. (Note: Sadly, Bob passed away Dec. 11, 2013. His obituary said he had visited 107 countries. Rest in peace, Bob.)

|

|

I could have ended my trip in Pierre, South Dakota. The superb people I met there made me feel very welcome and their kindness and support have me convinced the state’s capital city is an excellent place to live.

While I was in Pierre, I was invited to a BBQ at Patrick Wellner’s where he and his friends shared two important elements of American culture – grilling and football. After succulent steaks and tender pork chops prepared over coals by the Mustachioed Chef, we watched the game and had a few beers.

Elsewhere, I was fortunate enough to meet Shelley who owns Charlie’s Marina. She’s the guardian angel of paddlers in this part of South Dakota. Shelley took my picture to add to the framed images she displays in the marina of other paddlers who passed through this summer. She even let me borrow her car so I could get around Pierre.

Ken and Lynn Larsen helped me move my gear from the campground below Oahe Dam to the water’s edge. They share a love of travelling and I enjoyed our conversation about seeing the world.

I also met Calla LaPlante Morton as well as her mom and brother. We talked a lot about Sioux history such as the Lakota who stayed at Wood Mountain, Sask. She prepared a care-package of home-made soup, fresh salsa along with stew and biscuits.

You can understand why I didn’t want to leave Pierre, but the time had come for me to depart and begin canoeing on Lake Sharpe, the third of five reservoirs on my route that were created by damming the Missouri River.

Lake Sharpe technically starts below Oahe Dam, which is 6 miles upstream, but the current through Pierre is as strong as a river. Patrick arrived with his 17’ kayak on the morning of Sept. 15. We paddled until noon when we stopped for a shore lunch and enjoyed the delicious food Calla had cooked.

I thanked Patrick for all his help from the portage over Oahe Dam to driving me to the grocery store as well as for introducing me to his friends. He said it was no problem at all and then turned into the current and kayaked towards Pierre while I canoed with the flow that would take me to the next dam nearly 80 miles away.

The dominant feature of Lake Sharpe is the Big Bend. According to some, this peninsula is shaped like a turkey’s head with the beak pointing west. The bird’s profile is 25 miles around. Even though the neck is only 1.5 miles across, it would be exceedingly difficult to portage like I did at Little Bend peninsula where the gradual slope is only 60 to 80 feet high. The Big Bend is a steep and rugged 200 feet. A portage is theoretically possible, but I was content to let the south wind push me along to the tip of the turkey’s beak where I had lunch Sept. 18. For the rest of the day, I continued east along the top of the bird’s head until I reached the point where Lake Sharpe turns south.

I tied my canoe to the dock at the day-use area and set up my tent next to a pic-nic shelter. My guide book indicated I was now 1000 miles away from St. Louis. That’s still a long way, but it was encouraging to know the slowest part was coming to an end. After Lake Sharpe, there are only two more lakes before I reunite with the robust current of the undammed Missouri.

I could describe Sept. 19 as “windy,” but that wouldn’t transmit the violence of the gusts. The night before, I had tied my tent to the pic-nic shelter to keep the Nor’Wester from flattening it against the ground. The storm lines did their job, but when it came time to take down my tent I couldn’t escape the evil wind. I tried so many tricks to roll it or fold it, but the wind always unfolded the tent or inflated it like a parachute. My anger rose, but there’s no getting even with the wind. Taking down a tent shouldn’t be so difficult. If I had been watching someone struggle in my place, I would have laughed great big belly laughs. I finally accepted defeat and stuffed the tent into a black garbage bag.

But the fun wasn’t over. The wind pushed me sideways as I walked to the dock. I spat the grit out of my teeth and squinted as clouds of fine sand tried to carry my hat away.

I descended the turkey's neck heading south and stayed very close to shore. The cattails gave me a narrow gap of wind protection. They swayed and buckled under the 45 mph winds, but did managed to keep me, for the most part, from feeling it.

The town of Lower Brule is at the base of the neck. The lake turns east there. This could put me in a potentially difficult situation. The wind would allow me to sail very fast, but the wind had also pushed the waves for miles from the top of the turkey's head down its neck to Lower Brule. The distance and force of the wind was creating huge waves and I wouldn't be going with them, but across them. I wasn't sure this would be possible and told myself I'd give it a try around Lower Brule and continue if possible or stop if need be.

I angled east and let the wind surge me forward. The dam was only 7 miles away and at the speed I was going I could cover the distance in less than an hour. Then it happened. A giant wave picked me up and I teetered on the summit before the wave broke and my canoe leaned to the right, then more to the right and I began to feel that roller-coaster sensation in the core of my chest that told me I couldn't lean anymore and would be tossed from the boat into the lake. My body was leaned all the way to the left to counter the effect of the wave. Just before I grabbed the side of the boat for added balance, the wave released me from its clutches. It was my fault. I had been sailing too fast in turbulent water and couldn't maintain balance at all times.

I had to ditch the sail and slow down. I pinned it to the bottom of the canoe with my feet and tried to paddle east along shore, now 80 yards distant, that was lined with boulders. I had my balance back and put every ounce of strength into my easterly course, but the waves were easily stronger. They lifted me and then dropped me again and again ever closer to the boulders, which would crush the canoe's hull if a wave body-slammed me onto them. I still had 5 minutes before that would happen, but could see disaster unfolding slowly.

I took a deep breath because I knew that would help me find a solution. I needed help from the only thing as strong, or stronger than the waves - the wind.

It was risky and I might capsize, but I tipped the sail up and the wind instantly filled the fabric as the nylon snapped loudly. The thin reins dug into my hand as I pulled back hard with my arm. I strained to keep the sail in my grasp as the canoe shot ahead.

I felt very focused and reminded myself to breath deeply. The waves were still big and dangerous so I used my paddle as a rudder to steer southeast. This direction allowed me to go somewhat with the waves, rather than across them, and it also got me passed the boulders to the sandy shore a quarter-mile away. It had been too close.

My mouth was very dry and I could feel the adrenaline weaken as I unloaded my gear on solid ground. The risk saved my canoe and my trip.

The next day was postcard calm. I canoed leisurely and stopped to explore some bays. One of them was littered with fossils of sea shells. As I approached the boat dock at the dam, I saw the perfect portage machine in the parking lot. I justified my plan by telling myself, “It’s not stealing if you put it back.” I was sure all my gear would fit in the bucket which I would raise a few feet and tie my canoe underneath. Unfortunately, a guy in coveralls climbed into the cab and drove away with my front-end loader.

I met a few fisherman at the dock including Craig Kindrat (who’s Canadian, but now living in South Dakota) and Percy from Lower Brule who let me put my canoe onto his boat trailer and my gear in the box of his truck for the short ride to the other side of Big Bend Dam and into Lake Francis Case.

By Sept. 21, I reached Chamberlain, S. Dakota where I picked up some mail from Canada and was able to check emails and send a few articles which weren’t due yet, but I wouldn’t have internet access for a few weeks. While in town, I met Jessica Giard, the editor of the Chamberlain Sun, who interviewed me about the trip and even drove me to get groceries. I laughed out loud when I saw what was stocked in the grocery store’s produce department.

The weather on Lake Francis Case was a true gift. It was warm and sunny with barely any wind. What wind there was could be avoided by staying close to shore.

On Lake Oahe, the shore tapers gradually to the water which means the wind can run downhill and blast you – there’s nowhere to hide. Lake Sharpe and Lake Francis Case have miles of 10 to 20-foot cliffs against the water’s edge that protect you from the wind as it passes overhead and disrupts the lake 60 or so feet from shore. There is an alley of calm.

There was one particularly windy day on Francis Case, but the wind and the direction of the lake coincided so well that I was able to sail 33 miles, my new personal best. This was Oct. 1. I got all the way to the dam around 9 pm with a little help from the nearly full moon. In the month since I’d sailed on Oahe under the night sky, I’d noticed an obvious shift from summer to fall. The cottonwoods were cloaked in their autumn colours.

Jessica had given me John Corey’s phone number. He is the campground manager at the dam and he met me the next morning. We loaded my outfit into his truck and drove to the other side of Fort Randall Dam.

There are two beautiful stretches of river after this point. Together, they are known as the Missouri National Recreational River. The first section starts at Fort Randall Dam and ends 39 miles later at the mouth of the Niobrara River. The second section is 59 miles and runs between Gavins Point Dam and Ponca State Park. Outside of Montana, they are the only two undammed and unchannelized portions of the river. Part of their reputation is founded on the beauty of their chalkstone cliffs and their relatively unchanged appearance since the passage of Lewis and Clark.

A few miles beyond Fort Randall Dam, I entered Nebraska, which runs along the south bank. South Dakota remained to my left and would all the way to Sioux City, Iowa, which is where I would meet my brother.

The days were a true Indian summer with daytime highs in the 25 C/80 F range with lows only dropping to 7 C/45 F at night.

The storm of Oct. 3 killed the Indian summer. It began with strong southern winds that prevented me from moving forward even though I had the advantage of current. By the middle of the afternoon, I was forced to go ashore and wait for the wind to die. It didn’t. But it began turning from the south to the southwest. I was ¾ mile away from a bluff, which is what the chalkstone cliffs are called locally. The near-vertical 100-foot bluffs would be an ideal windbreak, but I had to cross an unprotected section of the river that was under attack from the wind. I canoed towards the bluffs and saw tumbleweeds and sheets of sand being hurled skyward, but as I got closer to my chalkstone windbreak the gusts lost their violence. Beneath the bluffs, I was able to enjoy a few hours of calm. Then, the wind completed its 90-degree turn and came from the west. I uncoiled my sail and cut the surface of the Missouri River at a steady 5 mph towards Verdel State Recreation Area, my destination for the day.

The westerly wind began to build intensity, just as my weather radio had forecast. I saw the cabins and mobile homes of Verdel appear above the river’s edge 2 miles away. I covered the distance promptly. The wind was now at 30 mph and propelling me at 7 to 8 mph. The canoe was becoming hard to handle because of the combined effects of the wind pushing it forward, but also exerting pressure along its 16-foot side thereby tilting the boat sideways and also veering it off-course. The vagaries of the waves and current also influenced my canoe’s direction.

I knew I could manage until the wind got stronger, which it was clearly doing. I knew the park’s boat dock was ahead and I wanted to get off the river before the storm hit with full force. The water’s edge was lined with boat docks belonging to the cabin owners and I couldn’t tell which one belonged to the state park.

I felt like a conductor on a run-away train. I needed to stop and check my GPS to confirm where I was to dock, but I couldn’t consult my GPS and steer at the same time. The current, the wind and the forward momentum of my canoe laden with hundreds of pounds of gear, water and food meant no amount of back-paddling would stop me.

On two occasions, I tried to reach out and clutch a dock in an effort to stop long enough to consult my electronic map. This was a delicate operation because I had to be sure the nose of my canoe didn’t crash into the dock and explode into shards of tattered fiberglass. By the time I had aligned the canoe safely, one dock zipped past and then another. I maintained my focus and resolve and was determined on protecting my boat from a kamikaze collision, but I was also aware of the huge cottonwoods bowing their heads to the stronger and stronger wind.

I looked to shore and saw a brown outhouse. The dock below it had to belong to the state park. The wooden dock was bucking and bobbing against the wind and waves but its size and weight created an area of slacker water around it. I began to paddle in reverse and was ever careful to keep the front of the canoe clear of disaster. I noticed a piece of white rubber trim around the dock meant to protect boats. The rubber was torn and hanging loose at the tip of the dock. As I approached, I seized it with my right hand and spun the canoe against the side of the dock that was sheltered from the chaotic wind and waves.

In the process, I had cut off a motor boat that was lining up to a trailer which was backed into the water next to the dock. I explained the situation to the boater and his son who perfectly understood. Once ashore, they showed me their day’s catch of fish. That’s when the wind began shaking trees and tossing sand with all the gusto of the Great Depression. Off the water just in time.

The fishermen told me about a small bar and grocery store a few hundred yards away. A hot meal was in order.

While eating, I met Eric who asked about my canoe trip. When he heard I was going to New Orleans, he called over his friend Troy. The three of us talked about the journey and then we drove around the area. They showed me the effects of last year’s flood. The flooded river had deposited sand dunes everywhere and they were now drifting across the road and billowing in the air. It could have been 1932.

We visited some of the neighbours and stopped in at the home of an older couple who were preparing to watch the first presidential debate. Doing his best to provoke our hosts, Troy agreed with everything Obama said in the manner of a member of a gospel church, “Yes, that’s true,” and “Yes, he’s right.” Our hosts weren’t exactly Democrats. They said Michelle Obama could have acted in Planet of the Apes – without make-up. Troy’s comments got the desired effect. We left shortly there-after.

Outside, the wind was in full force and Troy said, “You’re not sleeping in a tent tonight, you can stay at my place.” I wasn’t about to argue.

The wind churned the river all night and reached speeds of 45 to 50 mph, but it didn’t matter – I was indoors.

The next morning was cold and still a bit windy, but nothing like before. Troy gave me a ride back to the bar on his way to work. I had planned to have a hot breakfast and wait out the wind until noon, but by 10 I got sick of waiting.

The temperature had dropped significantly so I put on lots of layers with my rain gear on top to cut the wind. I wouldn’t describe the day as pleasurable, (miserable is more accurate) but the wind did help me sail quickly and safely towards the cabin community of Running Water, which is where the Missouri River passes through 8 miles of marsh before entering Lewis and Clark Lake.

I camped at Running Water and woke up around 6:30 Oct. 5 to the first frost of the trip. I wanted an early start so I’d have lots of daylight to get through the cattails and reeds. The forecast called for calm in the morning with increasing wind around noon. Although the tips of my fingers were freezing, leaving before the wind caused ripples and waves would help me see the main current. It would also prevent me from getting stuck or trapped in an area of low water or from entering places in the marsh where the river flowed in but not out.

My guide book and GPS both contained information from before the 2011 flood, which had considerably altered the main current’s path through the marsh. I talked to several locals, but none seemed confident in their knowledge of the channel’s strongest path towards the lake.

The main current is where water travels fastest. It also carves the river bed and is deep enough to allow boats to pass without obstruction. Without the main current, the flow becomes very slow and weak. Marshes trap sediment and can be very shallow in places. Staying in the main current means you’ll go faster and will have enough depth to float a canoe. The main current is also like a guide. If you hold its hand, it will lead you into the lake because that’s where it’s going. My guide delivered me to Lewis and Clark Lake around 2 pm.

The lake is only 28 miles long and I completed the crossing in 2 days. At the end, I reached Gavins Point Dam, which is a very significant point in the journey to New Orleans. It marks the end of the dammed Upper Missouri. After Gavins Point, there are no more dams or reservoirs – ever!

I entered the Dammed Upper Missouri August 4. It was now Oct. 6. In just over 2 months, I had passed through a chain of 5 huge reservoirs spanning three states and 620 miles. The hardest, slowest part was over!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1mKpjHaZTM&feature=context-cha

On the other side of Gavins Point Dam, I was surprised by the number of people who were there for paddlefish season. Because paddlefish don't take bait, anglers pull unbaited treble hooks through the water and hope that a fish happens to be swimming by. This method is called snagging.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wYbLDcBcIls&feature=context-cha

Below the dam, I got back on the Missouri National Recreational River and enjoyed great sailing weather, but I could have done without the below-freezing temperatures at night. The river was wide and lined with towering bluffs and hills covered in a range of deciduous trees whose changing leaves celebrated autumn. However, the river’s character changed after Ponca State Park. That’s where I saw my first mile marker. It was a blue panel with white numbers simply stating “750,” the distance to the confluence with the Mississippi. From here, the river is lined with crushed stones, known as rip-rap, and wing dams meant to prevent erosion, maintain current and depth and basically allow barge traffic. The Dammed Upper Missouri was no more. I was now in the Channelized Missouri River and would be all the way to St. Louis. This transformation of the river’s character was as significant as reaching Lake Sakakawea or Gavins Point Dam. The channelized river would flow much faster and I would have strong current all the way to the Mighty Mississippi.

I met my brother Michel Oct. 12 in South Sioux City, Nebraska, which is located at the tri-state junction of Iowa, South Dakota and Nebraska. My brother is named after my uncle and so it is fitting that he is part of Canoe to New Orleans. Despite a cold morning and windy weather, we were able to paddle 27 miles. While looking for a camp, Michel noticed an American flag and a cross on the other side of the river. We wondered what it meant.

The next day, we talked to a couple who were checking the lines they had set for catfish. The husband told us his brother had died of cancer and the family spread his ashes on the point of land where we saw the flag and cross. Michel and I canoed into Decatur, Neb. and made a shrine of our own, as we explain in this video. (The wind cuts him off at the end, but to paraphrase my brother says that Uncle Mitch was very generous and gave him a hockey stick from the Montreal Forum that our grandfather got there in the 1930s. He also says our uncle was always giving away his most precious items to the people he loved.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0-OQf48Rpg8&feature=context-cha

On Saturday, we looked for someone who could give Mitch a ride back to South Sioux City where he had left his rental car. We had one lead, but the person wasn’t leaving until Monday morning and my brother was hoping to leave Sunday afternoon. Sunday morning, we looked for a ride at the Catholic church. Within a few moments of entering, we were standing in a circle with the parishioners explaining the purpose of Canoe to New Orleans. We accepted an invitation to the community hall and shared coffee and snacks with the welcoming residents of Decatur. Thanks again to the Connealys for sharing how heart disease has impacted them and for giving Michel his ride.

I said goodbye to Mitch Sunday afternoon and eased into the current as he stood on the dock and took a few pictures. Before rounding a bend, I waved to him with my paddle and then floated out of sight.

Michel had brought a small glass lantern with him that once belonged to M'Nonc. I'll let him explain what he did with it,

"After you left, I ended up bringing my offering, the little lamp, to the banks of the river and threw it right in. I thought it to be something of an offering to the river, making Mitch a part of it, to bless those who travel on it."

The warm weather returned Oct. 16 with the high reaching 25 C/80 F. I canoed passed many barges loaded with stones. Other barges carried bull dozers and track hoes that were pushing or dropping stones along the shore to repair the damage to the rip-rap and wing dams caused by last year's flood. The channelized section is where I began seeing more heavy industry along the water.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TaQhau8kuGg&feature=plcp

I arrived in Omaha on the 16th and would need a few days to update the website, check emails, send articles and resupply before continuing to Kansas City.

While I was in Pierre, I was invited to a BBQ at Patrick Wellner’s where he and his friends shared two important elements of American culture – grilling and football. After succulent steaks and tender pork chops prepared over coals by the Mustachioed Chef, we watched the game and had a few beers.

Elsewhere, I was fortunate enough to meet Shelley who owns Charlie’s Marina. She’s the guardian angel of paddlers in this part of South Dakota. Shelley took my picture to add to the framed images she displays in the marina of other paddlers who passed through this summer. She even let me borrow her car so I could get around Pierre.

Ken and Lynn Larsen helped me move my gear from the campground below Oahe Dam to the water’s edge. They share a love of travelling and I enjoyed our conversation about seeing the world.

I also met Calla LaPlante Morton as well as her mom and brother. We talked a lot about Sioux history such as the Lakota who stayed at Wood Mountain, Sask. She prepared a care-package of home-made soup, fresh salsa along with stew and biscuits.

You can understand why I didn’t want to leave Pierre, but the time had come for me to depart and begin canoeing on Lake Sharpe, the third of five reservoirs on my route that were created by damming the Missouri River.

Lake Sharpe technically starts below Oahe Dam, which is 6 miles upstream, but the current through Pierre is as strong as a river. Patrick arrived with his 17’ kayak on the morning of Sept. 15. We paddled until noon when we stopped for a shore lunch and enjoyed the delicious food Calla had cooked.

I thanked Patrick for all his help from the portage over Oahe Dam to driving me to the grocery store as well as for introducing me to his friends. He said it was no problem at all and then turned into the current and kayaked towards Pierre while I canoed with the flow that would take me to the next dam nearly 80 miles away.

The dominant feature of Lake Sharpe is the Big Bend. According to some, this peninsula is shaped like a turkey’s head with the beak pointing west. The bird’s profile is 25 miles around. Even though the neck is only 1.5 miles across, it would be exceedingly difficult to portage like I did at Little Bend peninsula where the gradual slope is only 60 to 80 feet high. The Big Bend is a steep and rugged 200 feet. A portage is theoretically possible, but I was content to let the south wind push me along to the tip of the turkey’s beak where I had lunch Sept. 18. For the rest of the day, I continued east along the top of the bird’s head until I reached the point where Lake Sharpe turns south.

I tied my canoe to the dock at the day-use area and set up my tent next to a pic-nic shelter. My guide book indicated I was now 1000 miles away from St. Louis. That’s still a long way, but it was encouraging to know the slowest part was coming to an end. After Lake Sharpe, there are only two more lakes before I reunite with the robust current of the undammed Missouri.

I could describe Sept. 19 as “windy,” but that wouldn’t transmit the violence of the gusts. The night before, I had tied my tent to the pic-nic shelter to keep the Nor’Wester from flattening it against the ground. The storm lines did their job, but when it came time to take down my tent I couldn’t escape the evil wind. I tried so many tricks to roll it or fold it, but the wind always unfolded the tent or inflated it like a parachute. My anger rose, but there’s no getting even with the wind. Taking down a tent shouldn’t be so difficult. If I had been watching someone struggle in my place, I would have laughed great big belly laughs. I finally accepted defeat and stuffed the tent into a black garbage bag.

But the fun wasn’t over. The wind pushed me sideways as I walked to the dock. I spat the grit out of my teeth and squinted as clouds of fine sand tried to carry my hat away.

I descended the turkey's neck heading south and stayed very close to shore. The cattails gave me a narrow gap of wind protection. They swayed and buckled under the 45 mph winds, but did managed to keep me, for the most part, from feeling it.

The town of Lower Brule is at the base of the neck. The lake turns east there. This could put me in a potentially difficult situation. The wind would allow me to sail very fast, but the wind had also pushed the waves for miles from the top of the turkey's head down its neck to Lower Brule. The distance and force of the wind was creating huge waves and I wouldn't be going with them, but across them. I wasn't sure this would be possible and told myself I'd give it a try around Lower Brule and continue if possible or stop if need be.

I angled east and let the wind surge me forward. The dam was only 7 miles away and at the speed I was going I could cover the distance in less than an hour. Then it happened. A giant wave picked me up and I teetered on the summit before the wave broke and my canoe leaned to the right, then more to the right and I began to feel that roller-coaster sensation in the core of my chest that told me I couldn't lean anymore and would be tossed from the boat into the lake. My body was leaned all the way to the left to counter the effect of the wave. Just before I grabbed the side of the boat for added balance, the wave released me from its clutches. It was my fault. I had been sailing too fast in turbulent water and couldn't maintain balance at all times.

I had to ditch the sail and slow down. I pinned it to the bottom of the canoe with my feet and tried to paddle east along shore, now 80 yards distant, that was lined with boulders. I had my balance back and put every ounce of strength into my easterly course, but the waves were easily stronger. They lifted me and then dropped me again and again ever closer to the boulders, which would crush the canoe's hull if a wave body-slammed me onto them. I still had 5 minutes before that would happen, but could see disaster unfolding slowly.

I took a deep breath because I knew that would help me find a solution. I needed help from the only thing as strong, or stronger than the waves - the wind.

It was risky and I might capsize, but I tipped the sail up and the wind instantly filled the fabric as the nylon snapped loudly. The thin reins dug into my hand as I pulled back hard with my arm. I strained to keep the sail in my grasp as the canoe shot ahead.

I felt very focused and reminded myself to breath deeply. The waves were still big and dangerous so I used my paddle as a rudder to steer southeast. This direction allowed me to go somewhat with the waves, rather than across them, and it also got me passed the boulders to the sandy shore a quarter-mile away. It had been too close.

My mouth was very dry and I could feel the adrenaline weaken as I unloaded my gear on solid ground. The risk saved my canoe and my trip.

The next day was postcard calm. I canoed leisurely and stopped to explore some bays. One of them was littered with fossils of sea shells. As I approached the boat dock at the dam, I saw the perfect portage machine in the parking lot. I justified my plan by telling myself, “It’s not stealing if you put it back.” I was sure all my gear would fit in the bucket which I would raise a few feet and tie my canoe underneath. Unfortunately, a guy in coveralls climbed into the cab and drove away with my front-end loader.

I met a few fisherman at the dock including Craig Kindrat (who’s Canadian, but now living in South Dakota) and Percy from Lower Brule who let me put my canoe onto his boat trailer and my gear in the box of his truck for the short ride to the other side of Big Bend Dam and into Lake Francis Case.

By Sept. 21, I reached Chamberlain, S. Dakota where I picked up some mail from Canada and was able to check emails and send a few articles which weren’t due yet, but I wouldn’t have internet access for a few weeks. While in town, I met Jessica Giard, the editor of the Chamberlain Sun, who interviewed me about the trip and even drove me to get groceries. I laughed out loud when I saw what was stocked in the grocery store’s produce department.

The weather on Lake Francis Case was a true gift. It was warm and sunny with barely any wind. What wind there was could be avoided by staying close to shore.

On Lake Oahe, the shore tapers gradually to the water which means the wind can run downhill and blast you – there’s nowhere to hide. Lake Sharpe and Lake Francis Case have miles of 10 to 20-foot cliffs against the water’s edge that protect you from the wind as it passes overhead and disrupts the lake 60 or so feet from shore. There is an alley of calm.

There was one particularly windy day on Francis Case, but the wind and the direction of the lake coincided so well that I was able to sail 33 miles, my new personal best. This was Oct. 1. I got all the way to the dam around 9 pm with a little help from the nearly full moon. In the month since I’d sailed on Oahe under the night sky, I’d noticed an obvious shift from summer to fall. The cottonwoods were cloaked in their autumn colours.

Jessica had given me John Corey’s phone number. He is the campground manager at the dam and he met me the next morning. We loaded my outfit into his truck and drove to the other side of Fort Randall Dam.

There are two beautiful stretches of river after this point. Together, they are known as the Missouri National Recreational River. The first section starts at Fort Randall Dam and ends 39 miles later at the mouth of the Niobrara River. The second section is 59 miles and runs between Gavins Point Dam and Ponca State Park. Outside of Montana, they are the only two undammed and unchannelized portions of the river. Part of their reputation is founded on the beauty of their chalkstone cliffs and their relatively unchanged appearance since the passage of Lewis and Clark.

A few miles beyond Fort Randall Dam, I entered Nebraska, which runs along the south bank. South Dakota remained to my left and would all the way to Sioux City, Iowa, which is where I would meet my brother.

The days were a true Indian summer with daytime highs in the 25 C/80 F range with lows only dropping to 7 C/45 F at night.

The storm of Oct. 3 killed the Indian summer. It began with strong southern winds that prevented me from moving forward even though I had the advantage of current. By the middle of the afternoon, I was forced to go ashore and wait for the wind to die. It didn’t. But it began turning from the south to the southwest. I was ¾ mile away from a bluff, which is what the chalkstone cliffs are called locally. The near-vertical 100-foot bluffs would be an ideal windbreak, but I had to cross an unprotected section of the river that was under attack from the wind. I canoed towards the bluffs and saw tumbleweeds and sheets of sand being hurled skyward, but as I got closer to my chalkstone windbreak the gusts lost their violence. Beneath the bluffs, I was able to enjoy a few hours of calm. Then, the wind completed its 90-degree turn and came from the west. I uncoiled my sail and cut the surface of the Missouri River at a steady 5 mph towards Verdel State Recreation Area, my destination for the day.

The westerly wind began to build intensity, just as my weather radio had forecast. I saw the cabins and mobile homes of Verdel appear above the river’s edge 2 miles away. I covered the distance promptly. The wind was now at 30 mph and propelling me at 7 to 8 mph. The canoe was becoming hard to handle because of the combined effects of the wind pushing it forward, but also exerting pressure along its 16-foot side thereby tilting the boat sideways and also veering it off-course. The vagaries of the waves and current also influenced my canoe’s direction.

I knew I could manage until the wind got stronger, which it was clearly doing. I knew the park’s boat dock was ahead and I wanted to get off the river before the storm hit with full force. The water’s edge was lined with boat docks belonging to the cabin owners and I couldn’t tell which one belonged to the state park.

I felt like a conductor on a run-away train. I needed to stop and check my GPS to confirm where I was to dock, but I couldn’t consult my GPS and steer at the same time. The current, the wind and the forward momentum of my canoe laden with hundreds of pounds of gear, water and food meant no amount of back-paddling would stop me.

On two occasions, I tried to reach out and clutch a dock in an effort to stop long enough to consult my electronic map. This was a delicate operation because I had to be sure the nose of my canoe didn’t crash into the dock and explode into shards of tattered fiberglass. By the time I had aligned the canoe safely, one dock zipped past and then another. I maintained my focus and resolve and was determined on protecting my boat from a kamikaze collision, but I was also aware of the huge cottonwoods bowing their heads to the stronger and stronger wind.

I looked to shore and saw a brown outhouse. The dock below it had to belong to the state park. The wooden dock was bucking and bobbing against the wind and waves but its size and weight created an area of slacker water around it. I began to paddle in reverse and was ever careful to keep the front of the canoe clear of disaster. I noticed a piece of white rubber trim around the dock meant to protect boats. The rubber was torn and hanging loose at the tip of the dock. As I approached, I seized it with my right hand and spun the canoe against the side of the dock that was sheltered from the chaotic wind and waves.

In the process, I had cut off a motor boat that was lining up to a trailer which was backed into the water next to the dock. I explained the situation to the boater and his son who perfectly understood. Once ashore, they showed me their day’s catch of fish. That’s when the wind began shaking trees and tossing sand with all the gusto of the Great Depression. Off the water just in time.

The fishermen told me about a small bar and grocery store a few hundred yards away. A hot meal was in order.

While eating, I met Eric who asked about my canoe trip. When he heard I was going to New Orleans, he called over his friend Troy. The three of us talked about the journey and then we drove around the area. They showed me the effects of last year’s flood. The flooded river had deposited sand dunes everywhere and they were now drifting across the road and billowing in the air. It could have been 1932.

We visited some of the neighbours and stopped in at the home of an older couple who were preparing to watch the first presidential debate. Doing his best to provoke our hosts, Troy agreed with everything Obama said in the manner of a member of a gospel church, “Yes, that’s true,” and “Yes, he’s right.” Our hosts weren’t exactly Democrats. They said Michelle Obama could have acted in Planet of the Apes – without make-up. Troy’s comments got the desired effect. We left shortly there-after.

Outside, the wind was in full force and Troy said, “You’re not sleeping in a tent tonight, you can stay at my place.” I wasn’t about to argue.

The wind churned the river all night and reached speeds of 45 to 50 mph, but it didn’t matter – I was indoors.

The next morning was cold and still a bit windy, but nothing like before. Troy gave me a ride back to the bar on his way to work. I had planned to have a hot breakfast and wait out the wind until noon, but by 10 I got sick of waiting.

The temperature had dropped significantly so I put on lots of layers with my rain gear on top to cut the wind. I wouldn’t describe the day as pleasurable, (miserable is more accurate) but the wind did help me sail quickly and safely towards the cabin community of Running Water, which is where the Missouri River passes through 8 miles of marsh before entering Lewis and Clark Lake.

I camped at Running Water and woke up around 6:30 Oct. 5 to the first frost of the trip. I wanted an early start so I’d have lots of daylight to get through the cattails and reeds. The forecast called for calm in the morning with increasing wind around noon. Although the tips of my fingers were freezing, leaving before the wind caused ripples and waves would help me see the main current. It would also prevent me from getting stuck or trapped in an area of low water or from entering places in the marsh where the river flowed in but not out.

My guide book and GPS both contained information from before the 2011 flood, which had considerably altered the main current’s path through the marsh. I talked to several locals, but none seemed confident in their knowledge of the channel’s strongest path towards the lake.

The main current is where water travels fastest. It also carves the river bed and is deep enough to allow boats to pass without obstruction. Without the main current, the flow becomes very slow and weak. Marshes trap sediment and can be very shallow in places. Staying in the main current means you’ll go faster and will have enough depth to float a canoe. The main current is also like a guide. If you hold its hand, it will lead you into the lake because that’s where it’s going. My guide delivered me to Lewis and Clark Lake around 2 pm.

The lake is only 28 miles long and I completed the crossing in 2 days. At the end, I reached Gavins Point Dam, which is a very significant point in the journey to New Orleans. It marks the end of the dammed Upper Missouri. After Gavins Point, there are no more dams or reservoirs – ever!

I entered the Dammed Upper Missouri August 4. It was now Oct. 6. In just over 2 months, I had passed through a chain of 5 huge reservoirs spanning three states and 620 miles. The hardest, slowest part was over!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l1mKpjHaZTM&feature=context-cha

On the other side of Gavins Point Dam, I was surprised by the number of people who were there for paddlefish season. Because paddlefish don't take bait, anglers pull unbaited treble hooks through the water and hope that a fish happens to be swimming by. This method is called snagging.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wYbLDcBcIls&feature=context-cha